CHAPTER TEN

Suffolk: Another War

When a book is read, events become telescoped and it is hard to keep

time frames in perspective. One chapter might detail events that were years

apart, or outline the entire life of a particular character. For the author's

purpose, the narrative may focus on only the good or on the negative events

in a persons life. Balance is lost, and a biased picture emerges. Such

a skewered vision has developed of Marianne over the years.

Harry Price decided there were roughly 2,000 paranormal events while

my mother was at Borley Rectory. If each event took an average of one minute,

about 33 hours of her life have been chronicled. Trevor Hall dug up several

tidbits about her life before and after Borley which might occupy another

33 hours. What about the rest? What else did my mother do from 1899 until

1946?

We know nothing of her 15 years near Belfast except for the birth of

Ian, and her reference to "The Trouble" between the Catholics

and the Protestants of Northern Ireland. Is this when she formed a dislike

for the English? What about her schooling - what subjects did she like

and which ones did she hate? I often heard her stun people with her knowledge

of Gaelic.

Her family life contained lots of music, and some public performances,

so she must have had some happy moments. On the other hand, she often chided

me for wanting to be too Irish, so she must have seen problems as well.

The mother of Howard Greenwood painted a fairly accurate picture of

the disdain felt for illegitimate children and teenage marriages in that

era. There were no such things as "welfare babies," and Aid to

Families with Dependent Children in 1915. Still, the Shaw family must have

extended its love, for Ian found a home with them and Marianne was not

cast out.

We do know that Britains were keeping an eye on Adolf Hitler during

the Borley years. His 11 million votes in 1932 were not enough to overcome

Hindenburg's 18 million votes, but the Nazis did gain a plurality

in the Reichstag with 230 seats. Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1933.

Before long, Britain was gearing up for the inevitable war. As Angus Calder

pointed out in The People's War, "It was in [1935] that a new

direction in state activity came as a clear harbinger of the immense apparatus

of control which would be necessary in the next world war. Rearmament began

in earnest."(1)

Gearing up for a wartime economy would put people back to work, but

for the middle 1930's the effects of the great depression meant great unemployment.

"Wherever we went," J.B. Priestly wrote in his 1934 English

Journey, "there were men hanging about, not scores of them but

hundreds and thousands of them."

Calder wrote, "Life became an indignity. The street corner and

the public library were the habitat of the hopeless."

Perhaps to compensate, giant dance halls, family cars, radios and movie

theaters blossomed. Priestly wrote that America was the birthplace of these

new ideas, which included, "factory girls looking like actresses."

One of the girls with munitions factory experience who wanted to be an

actress was - Marianne Foyster - a girl who loved everything American.

Fully one year before war was officially declared, Calder described

how in September of 1938, "Thirty-eight million gas masks were issued

to men, women and children - but none were available for babies. Fitting

on those grotesque combinations of pig-snout and death's head, sniffing

the gas-like odour of rubber and disinfectant inside them, millions imagined

the dangers ahead more clearly. Symptoms of panic appeared: a flood

of hasty marriages, a boom in the sale of wills, signs that people

were hoarding sugar and petrol. A great many people planned, and some made,

their getaways from the cities; Wales and the West Country entertained

a spate of refugees." (2) [Emphasis

mine.]

Still, the average Britain on the street didn't want to think about

what was coming. Calder reported "Such timid souls were comforted

by the testimony of astrologers and spiritualists, who asserted

confidently and unanimously that peace would be preserved."(3)

[Emphasis mine.]

Government, however, was ratcheting up toward the expected war. In April

of 1939, for the first time in British history, military conscription was

instigated during peace time. A trial blackout was held August 9. Parliament

enacted the Emergency Powers Act on August 24, which meant the government

could do as it pleased in defense of the realm. Dad told me many times that Mom's people had

large property over in England that had been taken over by the government and turned into a

training ground for tanks.

I don't know where he got this story from, but I should have taken a clue from this that she wasn't

from Maine.

True story or not, the psychological

impact of the Emergency Powers Act was real - the war held a pervasive

stranglehold on the people. Germany invaded Poland September 1, and Britain

declared war September 3.

Calder reported that "August and September 1939 saw the greatest

flood of marriages ever counted in British statistics. . . Young men, and

older ones, were swept into uniform, while the threat of bombardment swelled

a mighty exodus from the cities." He also noted, "During the

first weeks of war, observers were impressed with a bizarre phenomenon.

In the buses, the trains and the pubs of Britain, strangers were speaking

to one another." Mom said that was how she first met Dr. Davies -

at a train depot.

Calder discovered that in the two months prior to the war, upwards of

3,750,000 people moved out of the populated cities. His research on evacuated

children is an education: "When the children poured on to the railway

platforms on September 1st, 1939, they were marched into whatever trains

happened to be waiting until these were filled, in many cases with little

or no attempt to control their destinations."(4)

The children from some areas were not very clean, and sickness soon

spread. A sincere effort was made to keep the schools running, but "In

the cities, half a million children were left to run wild. Children whose

education was half complete took jobs. Others turned to hooliganism - so

often were public air raid shelters wrecked by children that the authorities

were compelled to keep them locked."(5)

Perhaps Marianne Foyster should have been praised for her part in caring

for those children she did accept into her home. In a 1956 letter to Ian,

she talked about a girl "I nursed for awhile." No other reference

to that girl has been found, but the word "nursed" is consistent

with other phases of Marianne's life. How many others did she care for?

It has been suggested that because she had an invalid "father"

- Lionel - she would not be required to fill any official position during

the war. Indeed, handling Lionel as he became increasingly incapacitated

would be a full-time job. However, the mother I knew was never one to sit

still, and being restricted to a home for long periods of time would have

increased her desire for outside activity.

No published volume has pointed out Mom worked as an usherette during

this time. Iris Owen described for me what it may have been like for Marianne

working in a theater:

In those days going to the pictures was very different than today. There

were two films - the feature and a "B" picture - a 20 minute

newsreel and 15 minutes of cartoons. Often in the larger cinemas [there

was] a live performance - usually by a band.

[There is no record of it] but there was a half hour devoted to live

entertainment, and it is possible - especially during war time - that the

usherettes, if they had any talent, were given a chance to perform in this

period.

Performances went on continually and people came and went all the while.

Once in you could stay as long as you liked - see the whole thing twice

around if you wished. Ice cream and boxes of chocolates were sold by pretty

girls, and the usherettes showed [customers] to their seats - you didn't

sit where you liked. The usherettes were often chosen for their looks,

and were dressed in smart uniforms. Many a young woman met her future husband

while ushering. The [girls] would show the interesting men to the back

seats, where they could flirt with them in between their ushering duties.(6)

Owen also talked about the idea Marianne may have "taken part in

some local amateur performances to entertain the troops." As Owen

pointed out, "There was a lot of opportunity for people with talent

to entertain during the war - people were starved for entertainment. There

was no television then, and radio entertainment was limited."

In later years, she would watch every Alfred Hitchcock movie and all his televisions shows. She would read all his anthologies. She coyly referred to him as "My Alfred." I find it absolutely fascinating that "Marianne" is credited as wardrober in 11 of his films made during the period 1934-37! I have no trouble believing it COULD have been my mother. [The Clairvoyant (1934), King of the Damned (1935), The Tunnel (1935), The 39 Steps (1935), Stormy Weather (1935), Sabotage (1936), His Lordship (1936), East Meets West (1936), It's Love Again (1936), Young and Innocent (1937), King Solomon's Mines (1937).

A 2005 movie from BBC Films matches precisely with the observation made by Owen. Mrs. Henderson Presents is positively delightful! There are so many lines and situations from this film that could be straight out of the life of my mother, including a joy ride in a bi-plane. She loved the theater and would have loved to run one, especially during WW II. Based on actual events and featuring the lives of real people, the story has many levels. The first layer is that of a refurbished theater brought back to life by running almost continuous entertainment - five shows every day. This was a new concept in England. The next layer was to politely display a little nudity. To pass the censors, the scantily clad actresses posed in tableau, not moving. Dancers and singers would weave a small thread of a story, but we all know why the audience was so charmed. Another layer was the family that grew up amongst the company. The girls were "properly looked after." During the blitz, many stayed overnight in the underground of the theater. The Windmill never closed, even during the worst bombings.

This was England during the Borley incumbency and for ten years

after. Mom told me several times she provided some sort of civil defense

service. Her story about being willing to bop a shouting male civilian

with a nightstick in order to prevent panic rings true. Everyone had their

part to play in the war effort - everyone. Calder described how in January

of 1939, handbooks were sent to every household in England describing various

war-time duties. "It was designed to check impulsive volunteering

by skilled workers and to help others to find the appropriate service,"

he wrote. "By midsummer, over 300,000 had volunteered for the armed

forces and there were one and a half million recruits for the Civil Defence

services."(7)

I am so disappointed I did not keep my mother's Service Prayer Book.

It would not only have led to some answers about her official war-time

capacity, but would also have provided a valuable balance to what her "other"

life was like. I don't have the original, but I did copy down the information.

It read:

SERVICE PRAYER BOOK

SHAEF

LONDON APO 72

204/206 77843

Marianne Fischer

WSAFIC HQ

RENDLESHAM HALL

B HUT

Home - Salmonhurst N.B. Canada

Stepmother - Maren Fisher

Home minister - Pastor Jensen

May 1942

If I fall let me be buried simply as a soldier.

No pompous

ceremonies of re-interment.

Death hath no dominion over us, for all are

the children of God - and Death is just going home.

I have been greatly loved by my family, and have greatly

loved them.

In God I believe and know that through the Redeemer I shall

live again.

Not war but the conquest of self is the answer to world sickness.

Yes, the prayer book does have some inconsistencies, such as the reference

to Canada, but the prayer itself is beautiful, and the serial number and

reference to SHAEF is invaluable. This one clue alone indicates Mom was

probably engaged in some responsible war effort, and may have served in

some capacity for the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces.

She was very fond of Dwight Eisenhower, and we once received a thank you

card from his wife Mamie. Mom sent a get well card to the then ailing president,

and I still have the reply.

As of this writing, I have not been able to track down the "WSAFIC"

acronym, but it is clear she was definitely serving her country - most

likely as a volunteer. I believe WSA could stand for Women's Service Auxiliary,

or WSAF could stand for Women's Service, Air Force

The reference to "No pompous ceremonies of re-interment" are

exactly consistent with her feelings 50 years later when approaching death.

She requested her remains be cremated with no services of any kind.

While rummaging through my mother's private papers when I was a teenager, I found the

following startling notations from the war years:

Sarto killed in action April

9, 1942

Father died April 19, 1942

George killed April 27, 1942

L.A.F. died April 29, 1942

House bombed April 30, 1942

buried 3 days under masonry

After intensive research in 1994, I was able to get in touch with all

the children Mom had adopted. Adelaide told me although she remembered,

"There was a bomb near to the house. One ceiling came down, possibly

1945," she did not remember anyone being buried in any rubble. She

may have been away at school, however. Mom remained terrified of sudden

noises the rest of her life, and could not watch war movies - they made

her physically ill. It was obvious from her behavior around me she actually

experienced the death and destruction of rocket and bomb attacks first

hand. She was not always removed to the safe realms of the countryside.

Obviously "George" and "Sarto" were close to Mom,

and loosing them must have hurt. I have not been able to identify either

person, but must conclude this is not the same Sarto who wrote some love

letters to mother in 1948.

Marianne's father died October 9, 1943, not in 1942. (8)

If "L.A.F." is Lionel Foyster, the date is off by three years

and eleven days. That every date on this piece of paper is in 1942, is

also puzzling. On the other hand, my mother was terrible at remembering

names and dates. Could this be an attempt decades later to remember some

key dates before they completely slipped her mind?

The prayer of a nurse

Perhaps Mom served as a medical assistant of some sort during the war.

One of her poems reads:

A NURSE'S PRAYER

Oh, dearest Shepard of the Sheep,

Bless all nurses who vigil keep,

Night or day with those who lie

On beds of pain, some soon to die.

Give us firm hands and kind.

Keep us pure in heart and mind.

And strength give us from day to day

To do the work that comes our way.

But most of all, O blessed Lord,

Keep us faithful to Thy word.

So with the blessed Physician, we

May serve with joy in eternity.

The poem is written in the first person, which tells me if Mom didn't

actually serve in an official capacity as a nurse, she at least identified

with the service they provided. It makes sense to me that she nursed some

ailing soldiers or civilians during the years 1939-1945, if even role-playing

the part of a care-giver.

Then too, the physical and psychological aspects of the war must be

considered. What was it like to simply survive from day to day? What did

people think about, and how did those thoughts influence their actions?

As Iris Owen told me, "It is especially important to put the events

in the context of the times - only then can you understand why Marianne

acted as she did." In June of 1995, Owen wrote to me:

You need to realize that there were thousands of children born to

foreign serviceman in England at that time. Authorities had to set up special

homes to accommodate them, and fostering or adopting was very easy - anyone

who would look after a child in any way was welcome. There were also more

than a million children evacuated to foster homes to escape the bombing

raids.

I understand from Marianne that your [natural] mother was already

married, but her husband (who was probably returning from overseas service),

refused to accept you, and insisted you be adopted. Marianne said your

mother kept the birth certificate and she had the baptismal one to register

you with the authorities. It is in fact likely that you were never registered

- many weren't, and the authorities were not likely to chase people up

at that time.

Owen then related her own experience that may very well have paralleled

that of Marianne's. She told me one reason I may have taken to her so quickly

when we first started corresponding in June of 1995:

I left the Women's Forces in February 1945 and started training in

the local hospital at Cambridge to be a nurse. One of my friends, who was

a trained child care worker, came also to Cambridge and became matron of

such a children's home as I have described. They had about 50 children

under the age of two - all children of servicemen whose mothers could not

keep them. They were up for adoption, and they came and went constantly.

In my evening off I used to visit my friend at the home and help bathe

and feed the babies. I did this for about two years until my friend changed

her job. Cambridge is only about 30 miles from Borley, but Marianne could

well have ranged that far in search for baby. You were born in October

1945 - I could have bathed and fed you at that time!

Owen went on to explain how Mom spent some of her time during the war

years:

Marianne lodged some evacuees - children who were removed from bombed

areas and sent to safe areas in the country by the government authorities.

Marianne would receive small allowances for the upkeep of these children,,

together with their ration and clothing books. She would not make a profit

from housing these children, but larger families could make rations go

round better, and there would be some advantages [to having many children].

In any case, Marianne - and Lionel - were fond of children and concerned

about their welfare in general.

I believe Marianne when she said that when she left for the U.S.

that she fully believed that her neighbor would report to the authorities

that she had left the children behind, and they would be reclaimed.

It is unfortunate, but very true, that many children in Britain during

the war years and immediately afterwards were ferried about from place

to place in search of safety, and had many homes during this period.

This certainly fits hand in glove with her later years of service at

Lutheran Welfare, Family Services, and the LaCrosse Committee on Aging.

Even while working at the Jamestown Sun she spent hours teaching dance

to children and arranging public performances. I would sometimes accompany

her, and we went to such places as the Crippled Children's Home in Jamestown.

In later years we sponsored a "dance" at the Senior Citizen's

wing at Saint Francis Hospital in LaCrosse. While she may have received

money for training the young dancers in Jamestown, we received no money

of any kind for the various performances in different places through the

years.

During a visit to Manchester, England in September of 1997, my friend

an author Pat Cody talked to people about the children of WWII:

"Family relationships were stretched and snapped by the war years.

Children were sent into the country to protect them from bombs; but they

fell victim to separation instead. Some were fortunate. They were taken

in by good, caring people and later reunited with a parent or parents.

Those weren't in the majority.

Many youngsters were taken in more as hired hands than sheltered by the

people who took them. Many never saw their parents again. Even those who

did rejoin a parent had often grown apart so that normal family feeling

no longer existed.

Orphanages were a convenient place to leave children when a woman could

no longer feed them. Food was in short supply as was clothing, money, jobs

that paid a woman. No longer was it unspeakable for a mother to leave a

child at an orphanage. She wasn't always in a position to retrieve the

child, either. Most women left their children because they truly believed

they would be better cared for, not because they didn't care about the

child. They were sincerely trying to do what was in the child's best interest.

This may be difficult to understand in terms of today's world, these women

of Manchester told me. You have to realize that the world then was strictly

one day, even one hour, of living at a time. No one knew if they would

be alive the next minute. Death was a constant companion more than a threat.

The old values no longer mattered with sheer survival in the forefront

of every thought. You did what you had to do to survive.

If you could place a child where someone was most likely to look after

it, whether you could or not, you were relieved of a major stress to do

so. Not because you didn't want to keep and protect your child, but because

the fear of being killed and the child left defenseless was a real and

present danger.

You learned to get on, get by, scrape together enough food to keep going,

and you acted in ways that made you feel you didn't even know yourself

any more. Your world was shattered beyond recognition, and you didn't have

confidence that it might hold together long enough for you to make it any

better. You didn't live, you existed.

What had [Marianne] learned as a younger woman in dealing with insecurity

and troubles? What tools for coping had she found? Leaving you at an orphanage

[in LaCrosse Wisconsin] wasn't a personal statement about you; it was a way to protect you when

she couldn't.

Like you, your mother was a human being fighting an uphill battle against

life and poor odds. She did the best she could then at every point in her

life, just as you do. Neither of you would make the same choices as the

other, for you aren't products of exactly the same factors.

Under these circumstances, official documents were not common.

Indeed, my unofficial "adoption" paper is a rare and treasured

record. It shows how much my natural and my new mother cared about me.

In addition to the problems with stray children during the first few

months of WW II, 140,000 patients were turned out of their hospital beds

to make way for expected bombing victims. No thought was given to whether

or not there would be relatives waiting to receive them. Did my

mother provide shelter for discharged patients?

The coversheet of The People's War indicated, "The 1939-1945

conflict was a 'total war' for Britain: no section of society remained

untouched by air raids, the shipping crisis, military conscription, and

the war economy." My mother was like everyone else in England, we

just don't know exactly how the war touched her life.

We do know that Harry Price found a ready audience for people sick of

war. One reviewer of Most Haunted House called it "A wonderful

antidote to a night of Blitzkrieg."(9)

The German connection

One curious puzzle has come to the surface in relation to my mother's

loyalties during WW II. She was very adamant about her brother being killed

by "fifth columnists." She told me traitors sabotaged his plane

and his flight never made it to Germany. I remember very clearly a beautiful

British memorial album she showed me dedicated to the memory of "Major

S. E. Fisher of the Flying Tigers." I was told this was her brother,

which was consistent with the story that her maiden name was Fisher. Years

later I wondered if perhaps this was the same "Sarto" her private

papers said was killed in action April 9, 1942. Perhaps she loved him as

a brother?

Her brother - so the story went - often told her "We aren't dropping

holy water" on the Germans whenever someone complained about the bombings.

She used to say, "The English peasants are a filthy lot,"

as she told stories about how they would use pitchforks on downed German

pilots. In contrast, she often told me how much good Adolf Hitler had done

for Germany. We never talked about the holocaust.

Then there were the stories about Germany she told the Murphys - and

the German words that crept into her letters. Besides addressing me as

"Libeling" in one message, she once wrote, "I'm glad that

you are happy and that you are having country air to breathe and a place

to expand your lungs. "Liebenstraum" is how the Germans put it."

Along with the verbal clues about how Hitler "Kept the trains running," at least one visible

clue traveled with us wherever we went. It was a coronation cup for Edward VIII. In later years,

my mother gave this small china mug to me without comment, and I was too polite to ask

questions. Years later I have tried to put this puzzle piece where it belongs, and the subsequent

questions are fascinating. Was she attracted to a man who was attracted to a married woman - a

man who gave up his throne for romance? Could it have been that she sympathized with this

good-looking Nazi sympathizer? We often parrot the words of a loved one, and eventually come

to believe them ourselves. Did her crush on Edward transfer itself to his admiration of Facism? If

only that cup could speak.

My mother's "German Connection" remains a mystery, but current

rumors suggest she had another brother - perhaps a half-brother - who was

a German spy. So far, there is no way to prove this allegation either way.

Trevor Hall researched her background for many years, and never said anything

about this rumor. Hall never confirmed that William Shaw had a second wife,

and therefore any step-children. He did find her brother of record - Geoffrey

- was a poultry farmer at Magheramorne, Belfast Ireland.

The Australian scandal

After learning in 1994 that I was an unwanted "war baby,"

another interesting tidbit came to the surface a few months later regarding

my infancy. Just before my mother died, her executor suggested that had

Marianne not adopted me, I would have ended up in Australia under terrible

circumstances. The wife of a BBC movie producer I had worked with confirmed

that, "Many orphans and children from children's homes were sent out

to Australia after the war to what people thought was a new life, but in

fact [was] to really bad situations."

June Watkins sent me some newspaper clippings explaining, "The

children were told their parents were dead. Parents were told that their

offspring had been adopted." In reality, tens of thousands of children

were sent to populate the empire of Great Britain with "good British

stock." Many of the children were found, and claimed they "suffered

years of neglect, beatings, and sexual abuse by the religious orders and

charities that were supposed to care for them."(10)

Hunger and forced labor were common fates for thousands of illegitimate

and unwanted children as late as 1967. Several of the victims committed

suicide. Many found it difficult to start families of their own. Fifty

years later when they tried to find their roots, they found the records

had been destroyed. A social worker named Margaret Humphreys became a champion

for hundreds, and managed to trace some families, but her on-going task

is formidable. Many parents and family members have died over the decades

since this "national scandal of enormous proportions" was perpetrated

on the innocent children. Time is literally running out.

The migration "was carried out in secrecy and against every legal

convention by up to 35 of the most respectable names in British children's

charities."(11) The resultant scandal

was documented in a 1993 television program "The Leaving of Liverpool"

on the BBC.

It was very sobering to read the awful stories of these children and

then realize that if it had not been for Marianne, my story would have

been horribly different.

Survival during war

What few stories Mom did tell me about the war years included those

about shortages. Eggs and milk were particular treasures, she told me.

She explained that one way to relieve a supply truck of its valuable cargo

would be to act as if you belonged and boldly walk away with an armload.

She once told me with a smile that was one way Dad "captured' a load

of eggs. It now appears Mom needed all those eggs to feed the several children

in her care.

Another story I was told on a computer bulletin board related how a

child in Humber, England "didn't even see an orange until he was 10

years old." Jerry Parker went on to explain how he had talked to "folks

that were in England during the war. The general population didn't know

whether they were going to live from one day to the next because of the

bombing. . . Every penny that the folks had after the war went to rebuilding

the country."

Parker and I discussed how wives and sweethearts must have felt watching

their husbands and fiancee's being shipped off to war. Anxiety and loneliness

must have plagued many a heart. It wasn't unusual for people to "escape

into their imaginations in order to retain their sanity," Parker told

me.

Iris Owen remembered that "an awful lot of people were either making

bigamous marriages during the war years, or were posing as married couples."

She told me that "You can have no idea of the upheaval to the social

life of the country that the war brought, and how much ordinary relationships

were broken. It is a little remembered fact that if a couple registered

at a hotel, and especially if they were service people, by law the clerk

was supposed to ask for proof of marriage and the police regularly checked

hotel records. Although this was supposed to be primarily for the detection

of spies, it was also meant to deter people from making false claims."

It must be remembered that a still young Mary Anne Greenwood had already

gone through one world war and watched a beloved husband disappear. The

Shaw family was not rich to begin with, and the combined stresses of two

world wars, a world-wide economic depression, an early pregnancy and the

loss of a husband, would have created hardships on any young woman. Is

it so strange to accept an occasional flight of fancy to escape from these

heavy burdens?

It has been suggested that the Shaw family tried to retain a semblance

of dignity through all these hardships, and I can very well imagine their

efforts to achieve a Victorian life-style matched the aura I was raised

in. We never had enough money, but that didn't stop Mom from trying her

level best to clothe me properly, see that I had an education, and generate

a sense of dignity with music, manners, and respectable behavior. We read,

we played chess, we discussed politics and current events, we ate out,

and we planned for a brighter future. All these things were a continuation

of her life-long struggles against tragedy, economic chaos, and dashed

hopes for a better life.

The September 9, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon of the United States has added an updated view of what might have motivated Marianne. Under desperate circumstances, people turn to one another for comfort in ways they would not normally do. As described in the October 1, 2001 Los Angles Times by Kathleen Kelleher, "terror

sex has become a means for some to cope with terrifying feelings of fear, vulnerability and sadness. . . . Post-disaster sex is similar to sex that happens before, during and after war, said Pepper Schwartz, a University of Washington

sociologist. There is a sense between departing soldiers and their partners that this sex may be the last. Many soldiers marry

before they are sent off to war, not because they are magically seduced but because of something more instinctual, Schwartz said."

In her autobiography My Many Lives, Iris Owen goes into some detail about the affects

of the war on Britain. It is not hard to imagine her experiences ran

parallel to those of Marianne in many ways.

As each page of her past has been opened to me, I identified the influence

it had on our life together. I have been able to see Mom on the assembly

line of the munitions factory. I have been able to see her leaning up against

a window, sobbing, and staring into the night wondering where her first

love had disappeared. I can see her struggles to fit in with gentry and

peasants as she learns to accommodate both with out insulting either. I

can sense her fears for her very life as she escapes one horrible bombing

attack only to be engulfed in another. All these images flash easily through

my mind and I wonder the lady was able to simply survive, let alone provide

for those she loved and cared for. That she didn't succumb to any number

of temptations and hopelessness is an extreme compliment to her intestinal

fortitude and faith God would bring a brighter day. I am extremely grateful

to her for all she gave me despite overwhelming odds.

As each page of her past has been opened to me, I identified the influence

it had on our life together. I have been able to see Mom on the assembly

line of the munitions factory. I have been able to see her leaning up against

a window, sobbing, and staring into the night wondering where her first

love had disappeared. I can see her struggles to fit in with gentry and

peasants as she learns to accommodate both with out insulting either. I

can sense her fears for her very life as she escapes one horrible bombing

attack only to be engulfed in another. All these images flash easily through

my mind and I wonder the lady was able to simply survive, let alone provide

for those she loved and cared for. That she didn't succumb to any number

of temptations and hopelessness is an extreme compliment to her intestinal

fortitude and faith God would bring a brighter day. I am extremely grateful

to her for all she gave me despite overwhelming odds.

Hall's investigation

What little

we do know about Marianne's life after Borley came through the research

of Trevor Hall. His investigation discovered that Marianne married Henry

Fisher February 23, 1935 in Ipswich. For the first five months of their

marriage, they lived at Borley. Marianne put down her age as being six

years younger than it actually was, and indicated her father was Leon Alphonse

Voyster. Hall discovered that Marianne also rented an apartment at 12 Gippeswyk

Road in Ipswich under the name Miss Marianne Voyster. A neighbor lady remembered

"an attractive dark-haired woman who 'called herself by all sorts

of names' and who was visited regularly by 'an old gentleman.'"(12)

Hall deduced the visitor was Santiago Monk.

What little

we do know about Marianne's life after Borley came through the research

of Trevor Hall. His investigation discovered that Marianne married Henry

Fisher February 23, 1935 in Ipswich. For the first five months of their

marriage, they lived at Borley. Marianne put down her age as being six

years younger than it actually was, and indicated her father was Leon Alphonse

Voyster. Hall discovered that Marianne also rented an apartment at 12 Gippeswyk

Road in Ipswich under the name Miss Marianne Voyster. A neighbor lady remembered

"an attractive dark-haired woman who 'called herself by all sorts

of names' and who was visited regularly by 'an old gentleman.'"(12)

Hall deduced the visitor was Santiago Monk.

The Fishers

moved to 4 Ancaster Road in Ipswich July 6, 1935. This address is very

close to the Gippeswyk Road apartment - just around the corner, in fact.

Reverend Foyster joined them in October. The place was too large and inconvenient,

and so by September 17, 1936, the entire family moved to 102 Woodbridge

Road East, Martlesham in Ipswich. They were the first tenants of the newly

built home, which was supposedly constructed with Fisher's money "more

or less to Marianne's requirements." At least, that was the way Fisher's

sister described it to Trevor Hall. The new place was a Victorian style

brick home in a "very good neighborhood" next to a golf club.

The Fishers

moved to 4 Ancaster Road in Ipswich July 6, 1935. This address is very

close to the Gippeswyk Road apartment - just around the corner, in fact.

Reverend Foyster joined them in October. The place was too large and inconvenient,

and so by September 17, 1936, the entire family moved to 102 Woodbridge

Road East, Martlesham in Ipswich. They were the first tenants of the newly

built home, which was supposedly constructed with Fisher's money "more

or less to Marianne's requirements." At least, that was the way Fisher's

sister described it to Trevor Hall. The new place was a Victorian style

brick home in a "very good neighborhood" next to a golf club.

Marianne

denied the house was built with Fisher's money. She said, "Johnny

never had any money at all. In fact, Johnny was out of a job. . . a great

part of the time that we were at the house on Woodbridge Road. It was Lionel's

money. He had an insurance policy that came due at that time. It was quite

a modest little house." She continued:

Marianne

denied the house was built with Fisher's money. She said, "Johnny

never had any money at all. In fact, Johnny was out of a job. . . a great

part of the time that we were at the house on Woodbridge Road. It was Lionel's

money. He had an insurance policy that came due at that time. It was quite

a modest little house." She continued:

There was a saying that there was a room in the roof that Lionel

was locked in. Well, that's a damn lie. I used to take Lionel to church

in the wheel chair, and I'm trying to recall the name of the church. It

was an Irish rector who knew the Bulls. I used to take [Lionel] around

many places, and he was visited by Reverend Harrison and another clergyman

there in Ipswich.

His room was on the ground floor. It had French doors and went out

on to the garden. There were two little bedrooms in the upstairs. He never,

on any occasion was locked in. Lionel couldn't sit out in the garden -

there were too many houses all built around, and he objected greatly to

people staring at him and he didn't like it.

We thought when we went to Woodbridge Road that a small house would

be very desirable, but it wasn't. Then we heard about Hill Farm and we

went out to see it in the car.(13)

A neighbor remembered the Fishers used to take her father for occasional

rides in the car. The neighbor - Mr. Seaman - "offered the view that

Mr. Fisher was a rather strange, uncommunicative sort of a man. Apparently

the whole of his conversation with Mr. Seaman over a period of two years

was a 'Good morning,' on about three occasions. Mr. Seaman thought that

Mr. Fisher may have traveled in drapery, because for a short time Mrs.

Fisher opened a small draper's shop in Foxhall Road close by. The business

was a failure and it closed down after a few months."(14)

The draper's shop is never mentioned in any other resource. Mr. Seaman

remembered Mrs. Fisher had an Irish accent.

Henry's sister told Hall that their mother had stayed at Woodbridge

Road for three weeks, and never saw "Mr. Voyster." The mother

claimed she tried to visit his room when Marianne was gone, but always

found the door locked with no key available.

The sister also told Hall that Marianne neglected the children and admitted

to her "she loathed children and had neither time nor patience for

them."(15)

Conflicting information given to Hall indicated Marianne always wanted

children, and had even considered opening an orphanage. The marriage to

Fisher gave her the chance to fulfill her dreams. First one, and then another

adopted child was passed off as Fisher's own. He became suspicious, and

their relationship fell apart.

In passing, Hall correctly observed that Mr. Fisher also had

a stake in caring for the children. While Marianne is usually the center

of attention for abandoning the youngsters, Hall pointed out that both

Henry and his sister were "fully aware that Fisher had not fulfilled

his legal obligation to support the children [and] it seemed certain that

they would have purposefully refrained from letting Fisher's name appear

in any rate-book or directory lest he be traced by the police or the local

authorities in East Anglia."(16)

My mother told me many times, "All I have ever wanted is to be

a stay-at-home mom with lots of children." On the other hand, she

also spoke many times of "those brattin' kids," when watching

someone else's children. "Nney, nney, nney," was her epithet

to describe how children talked. "Greedy little buggers," she

called them. They were obnoxious. They always wanted something. She never

did resolve this emotional conflict.

Hall was able to locate Father J. Thompson who had served as priest

at Ipswich, and also at Rendlesham. Thompson remembered Marianne, but when

he and Hall compared notes, they noticed some discrepancies.

Thompson could not remember much about Fisher, but thought the couple

had plans to move to Canada at one point. He also remembered an American

soldier came to live with them as a paying guest. The priest "added

the spontaneous comment that it had struck him as odd that Marianne started

to cultivate an American accent during the last weeks at Martlesham."(17)

In 1954, some unsolved confusion was introduced to the investigation

when the priest told Hall he had seen letters from Marianne with Canadian

postmarks. She signed herself as O'Neil with the story she had remarried

after Fisher had died. Hall produced the O'Neil marriage certificate to

the surprised priest who said, "We thought that Fisher had died out

in Canada and that she had re-married out there. But your document throws

a different light on things. I suppose that in actual words she told the

truth, but she led us to believe a different story. It might be that it

was the American soldier that she married. She was always something of

a mystery."(18)

On June 24, 1938, everyone packed up once again for the move to Hill

Farm House, Chillesford. Standing alone about one mile from the eastern

coast of England, this house was quite large and reminded Hall of Borley

Rectory. The postmistress remembered the Fishers and the aging Foyster.

Hall made the footnote that "Every informant, without exception, greatly

over-estimated Mr. Foyster's age due to his rheumatism."(19)

Foyster was thought to have spent most of his time in bed, although

he was taken for occasional rides in a car. Fisher was gone for weeks at

a time. A military type was alleged to have visited more often "than

his duties could possibly warrant." Two children with the family were

thought to be "underfed and pitifully neglected." Many debts

were left unpaid when the family moved out.

This move was made May 23, 1940 when the family headed for The Whin,

Snape. Hall described Snape as being located in the "lonely"

eastern half of Suffolk. "The house was fairly modern," Hall

reported, "and built of brick and tile. It was quite large, and it

was curious that the house had an attic dormer window similar to that at

102 Woodbridge Road East."(20)

The owner was a Mrs. Irving, who remembered thinking the house was "much

too big" for an elderly clergyman, his wife, and two small children.

Marianne had "pleaded that they might have it." The name on the

lease was Foyster, and Mrs. Irving knew nothing of Fisher. (Most of the homes we lived in when we got to America, were also much to large for three people - an obvious pattern I missed while growing up. There were small places, but in all our moving about, the larger homes dominated.)

Mrs. Irving told Hall that Marianne had few callers. She also remembered

the police came around a few years later asking about Mrs. Foyster or Mrs.

Fisher. While Marianne had lived at Woodbridge Road and at Hill Farm House

as Mrs. Fisher, Hall was very puzzled why she reverted back to the name

Foyster while at Snape.

Hall's investigation later discovered Henry Fisher may have joined the

war effort about September or October of 1939. Fisher then supposedly moved

to Saxmundham, also in Suffolk. While there, Fisher was apparently hospitalized

with duodenal trouble.

About a year after

moving to Snape, everyone moved to Dairy Cottage, Rendlesham. It was June

3, 1941. That address remained the same until after Foyster died April

15, 1945, and Marianne married O'Neil.

About a year after

moving to Snape, everyone moved to Dairy Cottage, Rendlesham. It was June

3, 1941. That address remained the same until after Foyster died April

15, 1945, and Marianne married O'Neil.

In 1944 Marianne met Ian in London. Ian told Trevor Hall that he loaned

his mother £600 at that time so she could start a washing machine

business. Marianne only repaid £130 before leaving the country. Hall

doubted the veracity of Ian's tale for two reasons:

1. Washing machines were not readily available during this time period

when all metals were directed to the war effort.

2. Ian's professed dislike for his mother, even though he was making

good wages repairing damages caused by the bombs.

Ian told Hall it was at this meeting he saw acid burns on Marianne's

face. She told her son it was a result of a car battery exploding. Hall

did not believe that story either. I never saw any scars of such a burning,

and none are visible on any photos taken about that time.

Still known as

Mrs. Fisher, Marianne moved to Number 1, Deben Avenue in Martlesham September

21, 1945. The reason for the move was simple - Dairy Cottage had no running

water, and the only toilet was outside. Even when Lionel was alive, the

plans were to move to the first place that became available.

Still known as

Mrs. Fisher, Marianne moved to Number 1, Deben Avenue in Martlesham September

21, 1945. The reason for the move was simple - Dairy Cottage had no running

water, and the only toilet was outside. Even when Lionel was alive, the

plans were to move to the first place that became available.

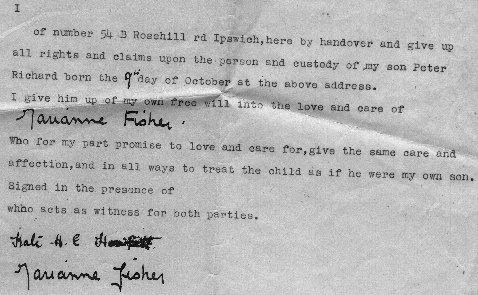

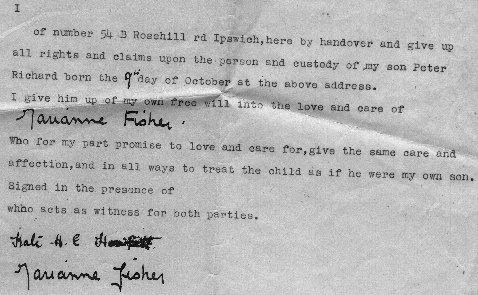

During her stay at Deben Avenue, Kate Helen Emma H------ came by

to collect premiums for the Prudential Insurance Company. Kate was pregnant,

and not quite sure if the baby belonged to her husband, William, or to

an American soldier. Mr. H------ wanted nothing to do with the child in

any case. Shortly after the child was born, Kate and Marianne signed the

following agreement, which was hidden from myself and investigators for

49 years:

For this photograph, I have smudged the original name, and deleted the

name of the witness.

Vincent O'Neil - February 2, 1946

Chasing clues

Following a discrete clue given him by Father Thompson, Hall eventually

found a former acquaintance of Marianne's in Woodbridge. This lady told

him one of the most startling stories of his investigation.

Mrs. J. T. Knights met Marianne at the Roman Catholic Church in Woodbridge,

just a few miles from Ipswich. She described Mrs. Fisher as "cultured,

well bred. . .graceful, physically attractive, and charming."

Marianne told Mrs. Knights her mother had died when she was quite young.

A second wife abandoned the family, leaving Marianne to care for her invalid

father. Mrs. Knights remembered her husband, Fisher, as "slightly

mental, but a nice enough man." Mr. Fisher was gone most of the time.

An American soldier named O'Neil was a paying guest.

After about six months, Marianne asked Mrs. Knights to babysit one of

the children while she went to Ireland. She needed to finish some business

in connection with the death of her father. Two other children were in

boarding schools, and an evacuee from the war had been returned to his

parents. Marianne would take the infant, Vincent, with her.

Mrs. Knights agreed, and when the appointed day arrived, Marianne left,

"just as if she were going to post a letter."(21)

After four days, Mrs. Knights went looking for Marianne, but found No.

1, Deben Avenue empty. The police were called. Mrs. Knights hired a solicitor

to track down Marianne, and apparently spent a great deal of money trying

to find her, but to no avail. By the oddest coincidence, the solicitor

was the same man Marianne had hired to settle Foyster's probate, Mr. C.J.

Parry. Hall did not tell Mrs. Knights of the coincidence.

Hall heard more from Mrs. Knights about Marianne, including the belief

she was a prostitute. One of the children told Mrs. Knights that with Fisher

gone most of the time, different soldiers stayed at the home "nearly

every night." Because there were not enough beds to go around, the

soldiers slept with Marianne.

The same child told Mrs. Knights how the children "were continually

knocked about and their life made thoroughly miserable." Marianne

apparently held their heads in buckets of cold water as punishment. As

Mrs. Knights told the story to Hall in 1954, she "was virtually in

tears as she told of her apprehensions regarding the treatment that 'little

Vincent would be receiving at the hands of that cruel woman.'"(22)

The father of the evacuee arrived in town a few days after Marianne

disappeared. He was enraged because Marianne had put his son, Tony Downing,

on a train toward his home with only a note attached to his button-hole.

In balance, the same child that talked about the buckets of cold water

later told me, "There were good times with [Marianne], as well as

the bad. She could be very loving and she put on some lovely Christmasses,

which was very difficult during war time."

The Knights family eventually adopted the child Marianne left behind,

and apparently renewed their friendship with Marianne. In 1954, Trevor

Hall believed the Knights had "never seen anything more of Marianne

since. . . she walked out . . . eight years ago [May 1, 1946]."(23)

Perhaps Mrs. Knights was trying to protect Marianne, for I know positively

she had contact with Marianne in 1947. Hall was not aware of the following

letter Mrs. Knights sent to Marianne which I found in my mother's papers.

It clearly indicates a continuing correspondence:

Kantara

Kingston Road

Woodbridge

Suffolk

18-3-47

My Dear Marianne;

Thank you for your letter of a few days ago, and I hope by now you

will have heard from me. Pleased you are keeping well, and glad Robin [Robert

O'Neil] has gotten over pneumonia alright.

I am thirsting for news of Vincie. You did not say how he was. Are

you able to see him often? Do tell me all about him.

We are well and keeping cheerful in spite of all the bad news of

floods, shortages of coal, and a black out. Girdlestones where Bob works

did not close down, and he is still working.

Sean is quite well. He brought some letters from Astrid when he came

for the weekend, which he should have let me have earlier (naughty boy).

Bob asked him how he would like Astrid to have forgotten his letters.

It is out of the question trying to get film for a Brownie [camera]

and if you could send me one or two I would be grateful. I would like to

send you some snaps of Sean. The camera is American made.

Sean seems to be growing very tall. He is growing out of all his

clothes. He cannot get his shoes on and has borrowed some one elses. In

fact, he came home in borrowed shoes, and his grey suit is completely worn

and too small. I patched and darned it during the weekend.

I forgot to mention in my last letter about the stone on your father's

grave [Lionel's]. Sean has pointed out one similar in Woodbridge Church yard, a flat

stone with just your father's name, and "priest."

The weather is much better and the snow nearly gone form here after

two months. We can again see the trees and grass are really green.

It will not be long now before your baby arrives, and I will be thinking

of you very hard the next month or two and wondering boy or girl. I am

so looking forward to the news.

I am so glad Robin's people are so good to you. It must be a great

comfort to you.

With fondest love to dear.

Letty

While friendly, the letter does seem to hint strongly some money would

be appreciated for at least children's clothing. I do know some funds were

sent, but I don't know how much and for how long. I have no knowledge of

whether or not my mother was pregnant in 1947. Although admirable in her

desire to protect Marianne, Letty's deception about not having contact

with her only strengthened Hall's conviction that Marianne was a criminal.

I can understand why Mrs. Knights cried during Hall's investigation.

Hall then found a neighbor to the Fishers at No. 8 Deben Avenue in Martlesham.

A certain Mrs. Nelson remembered that "Mrs. Fisher held herself aloof

from her neighbors and made friends with nobody."(24)

Mrs. Nelson paid close attention to her neighbors across the road, and

noticed they arrived with a great deal of furniture, including a piano.

Mrs. Nelson thought the furniture was sold piece by piece, to the extent

she wondered if the children might not be sleeping on the floor.

Marianne dressed well, including a fur coat. She also drove a car, which

was thought to have been eventually sold. Mrs. Nelson also remembered Marianne

pushing a pram, when no visits by any doctor had seemingly produced the

infant. Hall conjectured the infant was Vincent.

Hall came to the conclusion that Fisher never lived at Deben Avenue.

He decided Mrs. Shaw - Henry's sister - had "rescued" him while

still living at Dairy Cottage.

Hall also decided "It was becoming abundantly clear that Marianne

was an accomplished liar and probably a pathological one. He stories were

evidently convincing to persons of both sexes, but some of her deceptions

were pointless and dangerous. Even when the truth would have served her

best she seemed incapable of telling it. She did not scruple to lie to

the priest of her professed religion of Roman Catholicism."(25)

I found the following letter among my mothers papers that she must have

been very excited to receive during this time period:

American

Embassy

American

Embassy

1 Grosvenor Square

London, W1

February 7, 1946

Mrs. M.A. O'Neil

The Queens Head Inn

Woodbridge

Suffolk

Madam;

With reference to your application for an immigration visa and your

letter of February 2, 1946, the Embassy takes pleasure in informing you

that, by an Act of Congress approved December 28, 1945, alien spouses and

alien children of United States citizens serving in or having an honorable

discharge from the Armed Forces of the United States during the second

World War do not require visas to enter the United States, provided they

apply for admission before December 28, 1948. Physical examinations are

also no longer required.

It is understood that the military authorities are arranging to provide

transportation for the wives and children of military personnel. Inquiries

regarding transportation should therefore be addressed to the Adjutant

General, U.K. Base, United States Army, 47 Grosvenor Square, London, W1.

Private transportation may, of course, be arranged if desired.

The births of children who are American citizens should be registered

with the nearest American Consulate. They may travel on the Consular report

of birth and will not require passports.

Very truly yours,

Terry B. Sanders, Jr.

American Vice Consul

My new mother must have been flushed with joy as she headed for the

American consulate where she registered my birth:

Form 240

Report of Birth

Child born abroad of American parent or parents

London, England May 20, 1946

Name of child in full - Robert Vincent O'Neil, male

Date of birth - November 2, 1945, 2 p.m.

Place of birth - Nursing home 54B, Roseview Avenue, Ipswich, Suffolk, England

Father - Robert Vincent O'Neil

Born - February 22, 1920

Residence - Route 3, Caledonia, Minnesota

Birthplace - Houston, Minnesota

Mother - Marianne Emily O'Neil late Foyster, formerly Fisher

Born - January 26, 1913

Residence - Queens Head Hotel, Woodbridge, Suffolk, England

Birthplace - Romiley, Chesire, England

Exhibited - Certified copy of an Entry of Birth No. 462 issued

November 29, 1945 by P. Hammond, deputy registrar of births for District

of Ipswich in the County of Suffolk, England, showing birth of Robert Vincent

O'Neil, on November [blank], 1945.

Edith A. Stensby

Vice Consul of the United States of America at London, England

Until 1997, this has been the only document I have ever had to prove

my birth. When I asked the registrar for a copy of birth No. 462, I was

told no such recorded existed. Therefore, either the copy Marianne showed

to Edith Stensby was a fake, or Edith Stensby violated her oath by declaring

she had seen such a document when it did not exist. The Report of Birth

had a couple of type overs, including my birth date and the date of issue.

There is no number date attached to the last statement on the bottom which

supposedly confirms my birth date - " November [blank] 1945."

When I sent away for a duplicate copy of the Report of Birth, I was

shuffled from office to office. I still have not tracked down a copy of

Form 240.

There is a three month discrepancy between the date of the embassy letter

and the date the Report of Birth was filed. The possibility exists that

Marianne spent many restless days gathering together a sheaf of papers

she thought she would need to gain clearance back to the United States

- including a forged Service Prayer Book. When the Embassy told her how

easy it was going to be, she probably couldn't believe her eyes, but still

had to find a way to create a legitimate looking Report of Birth.

Trevor Hall had none of these documents during his search, and knew

nothing of the Woodbridge address at The Queens Head Inn.

There is no nursing home at 54B Roseview Avenue. Rather, it is a row

house in a less affluent part of Ipswich where Kate H------ sought refuge

to deliver her baby. It would seem Kate stayed there about

a month after my birth - October 9 - as she did not give me up until November

14.

Robert O'Neil's mother apparently told Marianne in a letter to be sure

and have a birth certificate for me before attempting to enter the States.

Mrs. Shaw saw the letter and told Ian about it.

Marianne left Deben Avenue May 1, 1946. She presumably headed for the transient center for war brides at Tidworth, Hampshire. She may have created a mailing address at the Queens Head Inn.

Chapter Eleven

Table of Contents

1. Calder, Angus. The People's War. New York:

Ace Books, 1969. p. 34.

2. Ibid, p. 28.

3. Ibid, p. 36.

4. Ibid, p. 43.

5. Ibid, p. 56.

6. Owen, Iris. Letter to the author, June 22, 1995.

7. Angus, op. cit. p. 58.

8. Alan Roper.

9. Daily Telegraph, October 2, 1940.

10. Braid, Mary. "The Shameful Secrets of Britains'

Lost Children." The Indpendent. London: July 13, 1993. p. 18.

11. Dalrymple, James. "How Britain Sent its

Children Into Exile." The Sunday Times. London: June 27, 1993.

p. 7.

12. Hall, Trevor. Marianne Foyster of Borley

Rectory. Unpublished, 1957. Vol. I, p. 50.

13. Hall, Trevor. Marianne Foyster of Borley

Rectory. Unpublished, 1958. Vol. V. pp. 51-52.

14. Hall, op. cit. Vol. I, p. 19.

15. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 70.

16. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 54.

17. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 34.

18. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 35.

19. Ibid. Vol. I, p. 31.

20. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 22.

21. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 40.

22. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 42.

23. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 41.

24. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 44.

25. Ibid, Vol. I, p. 45.

As each page of her past has been opened to me, I identified the influence

it had on our life together. I have been able to see Mom on the assembly

line of the munitions factory. I have been able to see her leaning up against

a window, sobbing, and staring into the night wondering where her first

love had disappeared. I can see her struggles to fit in with gentry and

peasants as she learns to accommodate both with out insulting either. I

can sense her fears for her very life as she escapes one horrible bombing

attack only to be engulfed in another. All these images flash easily through

my mind and I wonder the lady was able to simply survive, let alone provide

for those she loved and cared for. That she didn't succumb to any number

of temptations and hopelessness is an extreme compliment to her intestinal

fortitude and faith God would bring a brighter day. I am extremely grateful

to her for all she gave me despite overwhelming odds.

As each page of her past has been opened to me, I identified the influence

it had on our life together. I have been able to see Mom on the assembly

line of the munitions factory. I have been able to see her leaning up against

a window, sobbing, and staring into the night wondering where her first

love had disappeared. I can see her struggles to fit in with gentry and

peasants as she learns to accommodate both with out insulting either. I

can sense her fears for her very life as she escapes one horrible bombing

attack only to be engulfed in another. All these images flash easily through

my mind and I wonder the lady was able to simply survive, let alone provide

for those she loved and cared for. That she didn't succumb to any number

of temptations and hopelessness is an extreme compliment to her intestinal

fortitude and faith God would bring a brighter day. I am extremely grateful

to her for all she gave me despite overwhelming odds.  What little

we do know about Marianne's life after Borley came through the research

of Trevor Hall. His investigation discovered that Marianne married Henry

Fisher February 23, 1935 in Ipswich. For the first five months of their

marriage, they lived at Borley. Marianne put down her age as being six

years younger than it actually was, and indicated her father was Leon Alphonse

Voyster. Hall discovered that Marianne also rented an apartment at 12 Gippeswyk

Road in Ipswich under the name Miss Marianne Voyster. A neighbor lady remembered

"an attractive dark-haired woman who 'called herself by all sorts

of names' and who was visited regularly by 'an old gentleman.'"

What little

we do know about Marianne's life after Borley came through the research

of Trevor Hall. His investigation discovered that Marianne married Henry

Fisher February 23, 1935 in Ipswich. For the first five months of their

marriage, they lived at Borley. Marianne put down her age as being six

years younger than it actually was, and indicated her father was Leon Alphonse

Voyster. Hall discovered that Marianne also rented an apartment at 12 Gippeswyk

Road in Ipswich under the name Miss Marianne Voyster. A neighbor lady remembered

"an attractive dark-haired woman who 'called herself by all sorts

of names' and who was visited regularly by 'an old gentleman.'" The Fishers

moved to 4 Ancaster Road in Ipswich July 6, 1935. This address is very

close to the Gippeswyk Road apartment - just around the corner, in fact.

Reverend Foyster joined them in October. The place was too large and inconvenient,

and so by September 17, 1936, the entire family moved to 102 Woodbridge

Road East, Martlesham in Ipswich. They were the first tenants of the newly

built home, which was supposedly constructed with Fisher's money "more

or less to Marianne's requirements." At least, that was the way Fisher's

sister described it to Trevor Hall. The new place was a Victorian style

brick home in a "very good neighborhood" next to a golf club.

The Fishers

moved to 4 Ancaster Road in Ipswich July 6, 1935. This address is very

close to the Gippeswyk Road apartment - just around the corner, in fact.

Reverend Foyster joined them in October. The place was too large and inconvenient,

and so by September 17, 1936, the entire family moved to 102 Woodbridge

Road East, Martlesham in Ipswich. They were the first tenants of the newly

built home, which was supposedly constructed with Fisher's money "more

or less to Marianne's requirements." At least, that was the way Fisher's

sister described it to Trevor Hall. The new place was a Victorian style

brick home in a "very good neighborhood" next to a golf club.

Marianne

denied the house was built with Fisher's money. She said, "Johnny

never had any money at all. In fact, Johnny was out of a job. . . a great

part of the time that we were at the house on Woodbridge Road. It was Lionel's

money. He had an insurance policy that came due at that time. It was quite

a modest little house." She continued:

Marianne

denied the house was built with Fisher's money. She said, "Johnny

never had any money at all. In fact, Johnny was out of a job. . . a great

part of the time that we were at the house on Woodbridge Road. It was Lionel's

money. He had an insurance policy that came due at that time. It was quite

a modest little house." She continued:  About a year after

moving to Snape, everyone moved to Dairy Cottage, Rendlesham. It was June

3, 1941. That address remained the same until after Foyster died April

15, 1945, and Marianne married O'Neil.

About a year after

moving to Snape, everyone moved to Dairy Cottage, Rendlesham. It was June

3, 1941. That address remained the same until after Foyster died April

15, 1945, and Marianne married O'Neil.  Still known as

Mrs. Fisher, Marianne moved to Number 1, Deben Avenue in Martlesham September

21, 1945. The reason for the move was simple - Dairy Cottage had no running

water, and the only toilet was outside. Even when Lionel was alive, the

plans were to move to the first place that became available.

Still known as

Mrs. Fisher, Marianne moved to Number 1, Deben Avenue in Martlesham September

21, 1945. The reason for the move was simple - Dairy Cottage had no running

water, and the only toilet was outside. Even when Lionel was alive, the

plans were to move to the first place that became available.

American

Embassy

American

Embassy