CHAPTER SEVEN

Essex: Borley Rectory

(More excerpts from Marianne's Story by Iris Owen and

Pauline Mitchell.

Marianne resumes telling about the move to England.)

"We sailed away to England after spending some time in Salmonhurst.

We adopted Adelaide legally [there] through Anders J. Jensen. Once in England,

we went to Ireland for a short time, then we went to stay in private lodgings

in Cornard Magna, quite near the Bull residence. We attended Cornard church

which was high Anglican, and Lion really loved it.

"We visited often at the Bulls and we were glad of this opportunity.

The Bulls - first cousins of Lion's - were really delightfully different.

We really liked them, and they liked us. [emphasis added]

"We visited Borley Rectory and supervised some of the alterations,

or should I say renovations. We fell in love with the terrace garden, really

a sort of elevated rock garden. There was a cedar tree with a round flower

bed beneath it. Gerald Bull had started this bed many years before. It

was lovely in the spring with scillas, gray hyacinths, snowdrops, crocus,

and Star of Bethlehem. The narcissus and jonquils followed later.

"The rooms inside were enormous. The floors we varnished [as

well as] the front hall stairs. [It] really looked beautiful, but [it]

was hard to keep up.

"The rector's warden, Sir George Whitehouse, and Lady Whitehouse,

called upon us immediately. He had been knighted for a bridge he had built

in India. They were both plain people, kind and down to earth. They were

avid gardeners and Sir George grew -------- which had to be seen to be

believed. We met their sons, Langford and C'Bre, and visited Arthur Hall,

their residence. We met their nephew, Edwin Whitehouse.

"Edwin was a guest at Arthur Hall. He seemed to be at loose

ends, having given up a teaching position, and was attempting to discover

if he had a vocation. Edwin had been in World War I as a midshipman and

this had apparently taken toll of his nerves. Lion liked him very much;

so did I, for we found it pleasant to have someone friendly and uncritical

to talk with.

"Adelaide was lonely without other children. We answered an

ad in the Times, and from this we acquired a little boy named Francois.

He was a beautiful child, a few months younger than Adelaide, and we offered

him a month's vacation. But long before that time was up, Lion and I adored

him, and so did all who came in contact with him. [He had] big blue eyes

and brown curls, and an ever present smile. He was a chubby lad.

"At no time did his father pay us anything in the line of cash.

The father, Francois d'Arles, visited him every weekend at first. He did

some handy work around the place and was good about the garden.

"Lionel's health deteriorated rather rapidly, and we were somewhat

disconcerted by happenings taking place."

The following pages contain an account of the time the Foysters spent

at Borley, and events subsequent to this time. As this was the crucial

period, much time was spent discussing the alleged hauntings and Marianne's

recollections of the Rectory.

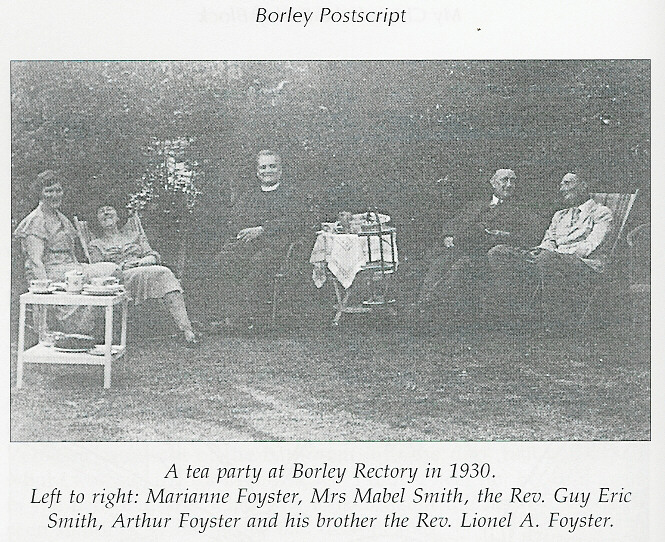

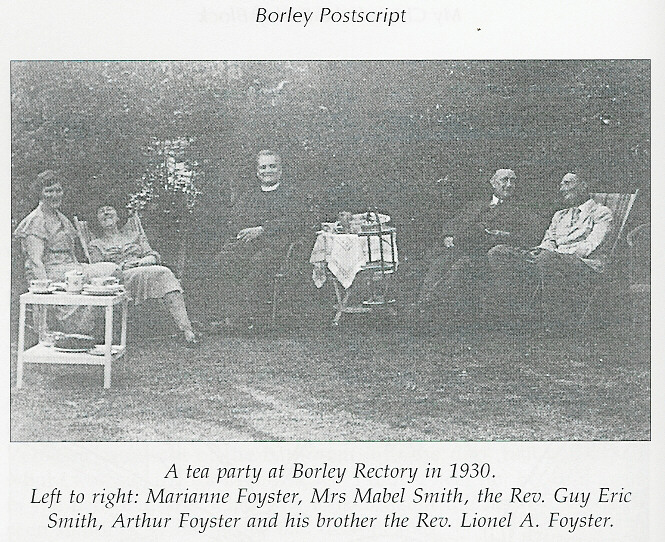

Of course the Foysters knew of the history of Borley before they

took the living; as well as hearing all about it from the Bulls when they

visited in 1924, and in 1926, they had met Mrs. Smith and heard from her

at first hand of the Smith's experiences. (Marianne said she felt Mrs.

Smith was confused, and felt that after being talked to by Harry Price,

Mabel Smith did not know what to believe!)

Of course the Foysters knew of the history of Borley before they

took the living; as well as hearing all about it from the Bulls when they

visited in 1924, and in 1926, they had met Mrs. Smith and heard from her

at first hand of the Smith's experiences. (Marianne said she felt Mrs.

Smith was confused, and felt that after being talked to by Harry Price,

Mabel Smith did not know what to believe!)

Marianne's own attitude when they went there was that it was a "lot

of tall stories," and she was impatient and annoyed at being stopped

by the local people every time she "put her nose out of the door"

to be asked for the latest. Probably Lionel Foyster got the idea of writing

a book about a haunted rectory as a result of the intense interest of the

local people - Marianne says he had the idea at an early stage. They were

not happy with the villagers, and especially the local gentry (with the

exception of the Whitehouses). The villagers thought they were too friendly

with the wrong kind of people - the lower classes. Lionel Foyster, especially,

was a man who was friendly to everybody; he fed the local tramps, and let

them sleep in the outhouses; he loved children; he adopted stray dogs and

cats, and kept an open house; doors were never locked, Marianne says.

[This is totally in keeping with her later activities in social work, especially

in LaCrosse, Wisconsin. While there, she opened a refuge for indigents

she called "Harbour Lights" - English spelling and all.]

The authors soon found there was no point in questioning Marianne

about detailed events that were alleged to have happened, as she stated

flatly that by far the majority were completely invented by Lionel, as

part of his book. However, she stated that from time to time odd things

would happen of a poltergeist nature, which would puzzle her, and which

she did not think Lionel or anyone else was responsible for. Footsteps

were heard when nobody really appeared to be around, and some of the things

that happened when Edwin Whitehouse was present bothered her. She felt

the wall writing originated in some way from him, although they would all

"reply" to the comments and questions - she specifically said

she herself wrote, as did Lionel and Ian, when he stayed with them on holiday.

But now, all these years later, she seems reluctant to believe that anything

was of a supernormal nature, and feels it was more likely that someone

was playing tricks. She believes Harry Price performed a magic trick when

he converted the wine, but does not accuse him of any other trickery.

. . . She still says she cannot understand why everybody made such

a fuss about a "bunch of tall stories," and finds it difficult

to believe anyone takes ghost stories seriously. . .

The Foyster Incumbency

Certain important factors have emerged during interviews and correspondence

with Marianne Foyster which shed a very different kind of light on the

happenings at Borley during the years the Foysters were in residence. For

some reason that has become recognized as the "key" period; the

time which has been regarded as affording most proof of the alleged hauntings.

The happenings during the Foyster incumbency were more of a poltergeist

type in nature, and the general view prevailing at the time was that either

this type of event was entirely fraudulent, or if the phenomena did occur

they were caused by "entities" or spirits, very often mischievous

or lying spirits, but spirits nevertheless.

It must be noted, however, that many of the events that took place

during the Smith's incumbency were of a poltergeist type, accompanied by

stories of ghostly apparitions, and the Foyster's experiences were, so

to speak, a continuation of what had been reported as having happened to

the Smith's. . .

But during the Foyster incumbency there was more than just a mild

poltergeist outbreak. From what Marianne has told us, three main strands

weave their way through the story of the Borley hauntings. First of all,

there were some inexplicable happenings of a poltergeist nature; secondly,

there was undoubtedly an amount of trickery; and thirdly, there was misrepresentation

and misinformation as to what actually happened. . .

It is important to understand that the over-riding and dominant factor

in the lives of the Foysters at that time was not the hauntings

and ghosts - it was the fact that Lionel Foyster was living through a death

sentence. He had returned from Canada knowing that his illness was

going to worsen progressively until he became helpless and bedridden, and

that he would finally die of this disease within the next 10-15 years.

He did die, in fact, 15 years after his return from Canada, following ten

years during which he was completely confined to wheelchairs or bed.

Marianne, his wife, was 21 years younger than him, and was 46 years

of age at his death. When the Foysters took the living at Borley, they

knew it would be a temporary arrangement, and they were concerned and anxious

about the future. They were aware it was only a question of time before

Lionel would be completely unable to continue his ministry.

Lionel Foyster was an educated, fun-loving man, with a tremendous

love of music and theatricals. Marianne has told us he always felt he could

have become a great actor if he had not been in the Church. This love of

music was the initial bond between Foyster and Marianne's family. Marianne's

father, Mr. Shaw, was an organist who had a great love of classical music.

He and Foyster collected...a small group of people who played and sang...together.

Marianne tells us all of her family were musically inclined. [Mom bought

very few records, but those she did buy were mostly classical. She also

taught herself to play several classical pieces on the piano.]

As a churchman, Foyster was a high Anglican, with a love of ritual.

He liked to write church music, and Marianne says he wrote new masses and

tried out new forms of communion services. He produced operettas, pageants,

and plays in his various livings, and much enjoyed this side of his work.

[Something she very much wanted me to do.] He took great pleasure

in training his church choirs himself; Marianne uses the word 'drilled.'

He was a man who throughly enjoyed his life and his church work.

But by the time they arrived at Borley, Foyster had become obsessed with

concern about his future, and was worrying about what would happen eventually

to Marianne and Adelaide. He became increasingly concerned about his financial

state; he had lost most of his own personal money in some venture in Canada

in 1928, Marianne told us. He would not be eligible for much in the way

of a pension when he left Borley, if indeed he received any at all.

In actual fact, Marianne says they were penniless when they left

the rectory and relied solely on what Fisher allowed her at that time,

and what she was able to make working as an usherette in the local cinema.

Marianne herself, of course, had very little training that would enable

her to earn a living. The whole of the Foysters life in England was lived

against the backdrop of this anxiety and concern about the future...

Lionel Foyster was well aware that Walter Hubbell had made a great

deal of money from the book he had written about the Amherst poltergeist,

and he conceived the idea of doing the same thing by writing a book about

Borley. This would solve his financial problems. The three documents, which

have been so extensively quoted in all the reports about Borley, were just

the bones of a story that Foyster was hoping to turn into a best-seller.

The Summary of Events was the basic plot, so to speak. The book

was to take on the form of a Diary - Fifteen Months in a Haunted

House would be the final title. Marianne says that everyone in the

household knew of this, and she believes that Harry Price was aware that

the accounts were mainly fictional. However, it seems that on the occasion

of his first visit to the rectory during the Foyster incumbency, Price

was shown Foyster's Diary of Occurrences and he reacted as if he

believed the account to be a truthful repetition of what had actually happened.

Price talked a lot about his own researches, including his work with Rudi

Schneider, and it was on the occasion of this visit that he accused Marianne

of being responsible for the phenomena. Both Foyster and Marianne were

upset that she should have been more or less publicly accused, and said

they did not want Price to visit again. It is not possible to ascertain

so much later in time whether Foyster actually told Price that the account

was fictional, or whether he deliberately allowed Price to believe it was

genuine, or whether, as is most likely, Price was aware of the fictional

nature, but it suited his purpose to pretend to believe it as truth.

Marianne describes Price as "a clever one," and is herself

of the opinion that Price must have known that the Diary was fictional.

However, Foyster was hoping that Price would endorse the book when it was

completed (a forward perhaps?) And he may have been uncertain as to how

Price would react to a purely fictional account, and so he may have left

the matter open. Foyster certainly wanted to make use of Price's expertise

and knowledge of the subject, and also of his assistance and contacts when

it came to publishing the book.

Foyster continued to correspond with Price after that first visit.

Marianne says it was against her wishes; she did not like or trust Price.

But, she says, Lionel could be obstinate, and he was obstinate on this

point. Price persuaded Foyster to lend him the Diary of Occurrences

in order that he could use some of the material in one of his own books,

and when he failed to return the manuscript some months later, Marianne

phoned Price to request its return. Price claimed that he lost it.

Foyster, however, still had his Summary of Events, and after

they had left Borley he recommenced writing the book, this time under the

title Fifteen Months in a Haunted House. This fact explains the

reason for some of the observed discrepancies in the various accounts.

Foyster, well aware that his account was fictional, did not bother

too much with minor details, or attempt seriously to reproduce the lost

Diary. After Foyster died, Marianne gave his books and papers to

his sister Hilda. Marianne says she wanted no part of them. In fact, she

was not very interested in the Fifteen Months manuscript while Foyster

was writing it; she regarded it as something to keep him amused while he

was confined to bed. Marianne assumes that Price acquired the Fifteen

Months manuscript from Hilda after she - Marianne - had already left

for the U.S.A. This would agree with the comments in the SPR report,

The Haunting of Borley Rectory, page 83, where Price, in a letter to

Dr. Dingwall dated October 17, 1946 is quoted as saying "I have now

acquired Foyster's complete Fifteen Months in a Haunted House."

[Peter Underwood requested Mom's permission to publish the manuscript

February 18, 1954. Unfortunately, her reply has been lost.]

As we have already said, it is difficult to be certain whether Price

was aware that this account was fiction or not. Price only visited Borley

himself twice during the Foyster incumbency. On the first occasion in October

1931, when he stayed overnight, and subsequently intimated that he believed

Marianne was fraudulently producing the phenomena; and again, on a later

occasion, when Marianne tells us, he arrived unheralded and uninvited,

following the report of a fire having occurred in the schoolhouse wing

of the rectory.

Marianne says Price heard of the fire through a lady in the neighborhood

with whom he corresponded, and turned up at the rectory doorstep. She says

he had others with him, and they brought a picnic hamper and wine, and

she places the incident of the wine becoming ink as occurring on this occasion.

She relates it as "one of Harry's magician's tricks," and did

not regard it as anything other than this. There was apparently a similar

incident when Price was dining with the Smith's.

Lionel Foyster continued to correspond with Price during the whole

time they were at Borley, feeding him with stories of the alleged happenings,

evidently to gain Price's opinion, and to obtain background knowledge for

his book.

It also seems that Foyster himself was personally responsible for

some apparent phenomena, probably produced for effect, to see how people

would react. Marianne says that Lionel threw objects many times, especially

when the group of spiritualists from Marks Tey were present. He threw things

in order to observe their reactions and to note what they would say. She

says the minute these people left the house, all such throwing of objects

stopped. The phenomena ceased completely when Lionel became confined to

a wheelchair.

Marianne says she herself was never sure who threw what, because

she says, other people would join in, particularly the village children.

Foyster's intention was not to frighten and deceive so much as to observe

and test people's reaction to the phenomena. Marianne says he would relate,

with great relish, stories of phenomena that were alleged to have happened,

and which the family members present knew were not true, in order to observe

his visitor's reactions.

In addition, the house was always wide open, the villagers came and

went; some of the rooms in the house were used for parish and church business

and meetings; the only toilet facilities were upstairs, thus affording

[an] excuse for people to wander all over the house, and much of the time

she did not know who was in the house or where they were.

She tells us that Lionel was very fond of children, and of the local

tramps and down-and-outs. These people were fed at the back door and allowed

to sleep in the outhouse. She believes that on cold nights they crept into

the kitchen for warmth. The house was never locked; the keys had long been

lost; the house had four outer doors and three staircases. They also possessed

a dog and a stray cat or two. One can understand how easy it would be for

anyone to produce fraudulent phenomena and it is equally easy to realize

that if any genuine phenomena took place they might not be recognized as

such.

Marianne says that sometimes there were events and happenings that

puzzled them. They did hear footsteps from time to time, when there

really did not seem to be any cause. Objects did sometimes appear to move

entirely on their own.

The wall writings were an example of phenomena that puzzled them.

These would initially appear, apparently from nowhere, although she admits

that she herself, and other members of the family "answered"

the remarks by writing underneath them. But she denies responsibility for

initiating them, and remarked that she was mad when they first appeared

as the wall had been recently redecorated and it took her hours to clean

it up. But she says the writings only appeared when Edwin Whitehouse was

in the vicinity, and she felt he was in some way responsible, either deliberately

or unconsciously.

Edwin was a very emotionally disturbed young man, judging from both

previous reports about him and from what Marianne says of him now. He was

obsessed with discussing religion, could not decide whether to become a

spiritualist or a Roman Catholic at one time, and he was always praying

and holding long conversations. He and Foyster played a lot of chess together,

and spent much time in each other's company. [Leading some to question

their sexual preferences.]

Marianne says Edwin was at a loss initially as to what to believe

about the "hauntings." He had been skeptical until he talked

to Harry Price, who apparently convinced him of the reality of paranormal

phenomena. Later, while in the rectory, he himself witnessed some phenomena

(see page 100 of SPR Report The Haunting of Borley Rectory), and

Marianne says he became totally confused about the reality of the subject.

She gives the picture of the three of them playing dice and word games

for hours in the evenings, when Lionel and Edwin would discuss the poltergeist

events and religion, and she observes, "Often I did not agree with

either of them." Again, there are two possible explanations, and one

can never be sure of the truth so long after the event. Edwin Whitehouse

could well have been the focus of such genuine poltergeist activity as

occurred, and this is probably the most likely assessment, especially since

Marianne herself says she witnessed some of these things when Edwin was

present and finds them puzzling.

But it is also possible (although perhaps less likely) that Edwin

was a confederate of Lionel's and would "create" phenomena when

Lionel was not there to do so himself. They were very close friends and

Edwin was continually at the rectory. Marianne says the meals at Sir George

Whitehouse's home were light, and Edwin had a healthy appetite - she fed

him at the rectory on most days.

It is also noteworthy that the poltergeist phenomena finally ceased

after Marianne says she pleaded that the house be "cleaned."

She wanted a religious service. Edwin arranged for a mass to be said, and

Lionel officiated at a religious service. This also coincided with the

time that Lionel became permanently confined to his wheelchair, and Edwin

had decided to become a Benedictine Monk, and left the village. From then

on the phenomena ceased completely.

Again we are left with the two possible explanations - the phenomena

ceased because Foyster could no longer throw things without being detected,

and Edwin left the neighborhood. It would be interesting to know whether

Edwin experienced continuing poltergeist phenomena in his monastery! We

cannot now decode whether Edwin was the center of genuine poltergeist phenomena,

or whether it was all trickery.

Marianne herself confirms that the events of the bottle, tumbler

and stiletto happened as described in the SPR report, but with the exception

of the wall writings, which she definitely attributes to Edwin's conscious

or subconscious self, she still thinks there is a possibility that it was

trickery. Edwin, of course, knew of the book, and that it was meant to

be a fictional account, and could have been, as we have said, a confederate

of Lionel's. . .

After the 'house-cleaning' [for ghosts] and Edwin's departure

to join the Benedictines, Marianne writes "the house stayed quiet.

Lionel's arthritis wasn't too bad. We built a doll's bungalow for Adelaide.

Lion and I played Snakes and Ladders with the children... Some really happy

months passed. Then Lionel's arthritis caused him to be hospitalized."

From then on the Foysters became increasingly concerned about Lionel's

health and their financial future. This was the period during which Marianne

tried various jobs, including the flower shop venture with d'Arles.

She started to foster children for long and short periods. These

children were mostly placed with the Foysters by the Church of England

Children's Society. This is a voluntary society run as a charity...which

looks after children in need, provides holidays for children from poor

areas, [provides] temporary foster homes for children whose parents are

sick, and runs an adoption agency for children of unwed mothers [when]

the mother is unable to provide for them.

The Society looks for accommodations for these children from among

members of the Church of England, and it was a completely natural thing

that the rector of the parish would be asked to help find homes for needy

children. The Foysters had already demonstrated their generosity in this

respect by their adoption of Adelaide before leaving Canada, and they started

looking after children again at this time.

Marianne told us that Lionel and she both loved children, and she

stated they 'did not receive a penny' for looking after the children they

took in at Borley. However it is very likely they received money for the

children's upkeep and clothing.

Marianne tells us that Lionel managed the family finances, and he

looked after the money form the flower shop. Marianne continued to take

in children right up until she left England, after Lionel had died. She

was looking after children [on] weekends who had been evacuated from the

bombed out areas of London. When asked what she thought would happen to

the children when she left for the U.S. she replied that she had thought

the Children's Society would reclaim them; 'they knew where they were.'

. . .The facts of Lionel's illness and its prognosis make a tremendous

difference when looking at the many suppositions put forward from time

to time about Marianne's possible motivations for fraud. Far from wishing

to leave the rectory, as has been alleged, they were happy there. She commented

to us that anyone who had lived under the circumstances of their early

days in Canada would regard living at Borley as a luxurious way of life.

The Misses Bull had had some extensive re-decorating done before they moved

in, and Marianne says she loved the place - especially the garden and the

grounds. [Our last home together on 16th Street in LaCrosse was definately

a throw-back to Borley. It was a large, two story house with a huge attic

and a basement. When Mom bought it, I think it went for $12,000 because

it was so run down. I put aluminum windows on the main floor, and she eventually

had to put on a new roof. Since I was off at school most of the time, it

was a huge place for just her and Dad. It also had an extra staircase,

and rooms we never used. She never stopped gardening until moving to the

retirement apartment in Utah. She loved flowers and tomatoes.]

But whether they had liked Borley or not, they had no money, and

knew that when they left Borley it would be because Lionel would no longer

be able to continue his ministry, and they would have no home to go to.

Since the rectory did not belong to them, they could not be accused of

trying to profit should its reputation for being haunted increase its value

in the real estate market!

. . . we feel that what Marianne has told us makes sense. It is logical,

and, what is more important, everything she has told us fits in with what

is already known about the Borley hauntings during the Foyster incumbency.

To us it has the ring of truth.

. . . if Lionel Foyster believed that as far as the Church was concerned

his marriage was not valid [because he was Marianne's "spiritual father"

having baptized her], this explains his subsequent acceptance both of Marianne's

"flings" as she describes them, and her bigamous marriage to

Fisher. . . there remained, as there had always been, a deep affection

between Marianne and Lionel Foyster, although this appeared at times to

be the relationship of a father and daughter, rather than that of a husband

and wife. . . Lionel Foyster had only about two years of good health after

their wedding! But, as we have said, their relationship was very close.

Marianne still speaks of him affectionately by her pet name of "Lion,"

and often uses the present tense when talking about him. He was clearly

the most important man in her life, and they remained married and together

for 23 years. She makes it clear that she never had any intention of abandoning

Foyster while he still lived in spite of her "flings." When she

"married" Fisher, Lionel was very ill, they had given notice

of leaving Borley, and she thought he might never come out of the nursing

home. . .Although she says Foyster knew that the marriage was bigamous,

she seems to believe that Fisher never knew the truth.

. . .one has to recognize that we are relating only what Marianne

has told us. There is no way of proving that one opinion as to the truth

of the matter is more believable than another, except by comparing the

accounts and trying to see which version makes most sense. . .Her own reaction

when first contacted was of dismay and horror. She wrote back to say that

she was "under the impression that I had at last achieved privacy.

I have suffered much at the hands of sensationalists. . .I was not a central

figure (at Borley). . .unhappily I happened to be there when the time was

right for the sensationalist to make heyday. . .I am the innocent victim."

. . .Marianne also told us of the interview granted to Mr. Robert

Swanson of the Parapsychology [Foundation] in May 1958. She gave us permission

to use these tapes if we wished, to check the story she is telling us now.

She said that during those interviews she had been questioned on a yes-no

basis, and remarked that the lawyer seemed more interested in her sex life

than on what really happened. She maintained that she had told him then

that most of the events alleged to have happened [at Borley] were fiction

and not fact. She said if she had been asked she would have related the

whole story then, but she felt she was being threatened, and decided to

only answer the questions put to her. Due to the generosity of Mrs. Babs

Coly, President of the Parapsychology [Foundation], we were furnished with

a transcript of those interviews, or rather with as much as remains, some

of the material having been lost during a flood in the basement of the

[Foundation]...

. . .In the interview in 1958 she allows it to be believed that Foyster

did not know of the existence of her son, Ian, and that he was passed off

as her younger brother... It would have been impossible for Marianne to

have pretended Ian was her brother and not her son, when her husband was

still in such close touch with her parents. Apart from that one instance,

there are no important discrepancies to the questions put by Mr. Swanson,

and the information Marianne has given us in the present interviews, letters

and telephone conversations.(1)

(Marianne's unpublished autobiographical outline continued.)

England

We arrived in England in August. London was hot and dowdy, and we

were glad to arrive at Sudbury where we were met by a cousin, Kathleen

Bull. After taking tea at Cornard Lodge, the home of the Bulls, we went

to the house where rooms had been taken for us. The cousins, Alfred, Gerald,

Kathleen, Freda, and Constance were all delightful people and we had a

nice afternoon visiting. When we went to the room, we found it in a typical

English villa of the middle-class. The landlady amused us highly by referring

to our adopted child - Adelaide, aged two - as "Miss Adelaide."

It was the first time in the life of Lionel or myself that we had

been confined in so small a space. The bedroom was small anyway, and with

the crib in for the baby, there was not room for us both to dress at the

same time. We decided that Lion should get up first and take a bath, and

while he was bathing I would get up and give the baby her breakfast, then

I would return upstairs and take my bath and give the baby hers. The landlady

was scandalized - I breakfasted in my dressing gown.

We could not bear to sit indoors, and there was no where we could

sit outside without being a public show for the natives, so we used to

take long walks, and this was thought to be a sign of supreme discontent.

We were constantly watched, and how the natives did stare at the sight

of Adelaide in little dungaree overalls. Perfectly proper in America, but

thirty years ago, Ah England! We took her everywhere with us and this was

considered very Un-English.

After the fashion of the new world, I wore lipstick. The natives

were scandalized. I decided not to use it, but Lion objected. He said if

I did, it would look like an admission of guilt. He did not like the fashion

of the English women with their naked faces. So I continued to use lipstick.

We were further suspect because we both had the American habit of

chatting with cottagers, postmen, milkmen - anybody who answered our smiles.

We sang a lot, as we had done in Canada, and in addition to hymns on Sunday,

we sang a lot of Danish hymns and songs. How dreadful it all was to the

landlady and her daughter Our greatest fault was the fact that we laughed

a lot, and Lion encouraged me to play popular songs. He liked them more

than I did.

There was on the one hand the Bulls, our cousins, who were darlings

and who treated us as spoiled darlings - and on the other hand were the

natives, who did not like us very much. I put my foot in it entirely by

being a far too good tennis player, and when I played golf, it was discovered

that I was better than most of the men. Lion took a particular pleasure

in this, and rubbed it into one or two of the men I defeated. He did not

tell them I was a winner of the Wood Champion Golf Cup in 1927 while we

lived in Sackville.

Lion was too democratic for the local clergy, and far too advanced

in his views. When they (the clergy) talked of the poor keeping of their

place, Lion used to really hit the ceiling. When he got angry, he was the

funniest man in the world. He wanted to swear and his conscience would

not let him, and then he would say "Jam and plaster, jam and plaster.

Wind and water," and I - according to custom - would chime in with,

"Putty eyes, stock and dies. Up the rebels and down with the church

and state. No home rule for Ireland." It was all very silly and yet

- when repeated by that landlady - who with her daughter listened at doors

- it sounded as if we were a dreadful pair indeed.

When Lion heard the gossip, he was very amused. I was not so amused.

I knew what the English were like. I'd seen them in action over in Ireland.

However, as things will, it passed. The incidents were mostly amusing at

the time, but Lion - being English - could not brook anyone disapproving

of him.

We sought to establish a residence, but all the houses we looked

at were either far too high in rent for us to afford, or they were too

far away from the parish at Borley. Many of the places were ghastly villas

with beetles in the basement. Others were farm houses, manor houses, and

"Gentlemans Places." We determined not to be discouraged, and

after a good deal of figuring and planning, we almost decided on living

- as the last rector had done - in Long Melford. Until one day Gerald Bull

- another cousin - said, "Borley Rectory was always such fun."

Hitherto we had not even looked at the rectory, but now, I persuaded

Lion to think about it. On the following Friday, Bernard Foyster, a cousin

- who had a say in the gift of the living since he was the family lawyer

and fellow patron of the living - came down to stay over the weekend with

the Bulls. He thought it would be nice to have a relative in the house

once more, and with us he looked over the house.

Both Lion and I were enthralled with the grounds. The house was large

- in fact it was huge - but not unwieldy for working since there were unlimited

cupboards, closets, wide halls, and plain rooms with no nasty cornices

and corners to collect dirt. It was a house built for family living when

families were large and servants plentiful. But, it was a house that fitted

into the American plan of shutting rooms off for the winter. We both of

us decided that we would look no further, but that we would make Borley

our home.

We consulted a local firm of contractors and they planned to make

the place habitable; it had been sadly neglected by the Smiths, who had

left the water turned on in zero weather with amazing results.

A cousin of Lion's, Mrs. Kitty Bull, offered to have us stay at Pentlow

and we thought of accepting, but Lion thought it would be a good time for

me to go visit my grandmother whom I had not seen for some years. She was

ill at the time and I knew she was not going to be with us much longer.

She died a few months later.

Lion went to Kitty's place and while there he had a lot of work done

on his teeth. He scandalized the local gentry quite badly, however, by

walking to Sudbury and occasionally accepting lifts in farm carts.

Lion wrote for me to be sure and go to Dublin to see the Abbey Players.

At that time we both had a friend who was keenly interested in the players.

I did not go, but I did see some fine players in Belfast, and got down

to business with them about the best plays for village production. Lionel

was very keen to have a production as soon as possible.

I did not stay the full two months we had planned on. The Rectory

was finished long before that time, and Lion went to live in it by himself,

and I could not allow him to live there alone. So I returned early in November

[by October 16, 1930] when the air was filled with the scents of

wood burning, and there was that hazy blue sky which speaks of good weather

ahead.

We had fun that first night at the rectory, running 'round exploring

and planning. We built a fire in the library and I produced play books

I had brought with me from Ireland. Lion got excited over one play, Maid

Marion, and could not make up his mind whether he wanted to produce that

or start immediately on a Christmas play. I counseled him to wait until

we were more firmly established. He was quite peeved with me, but soon

got over it and we played chess and bezique for a long time. We heard steps

overhead several times and we thought it was Adelaide getting up to go

toilet. She always did that at night. But when the feet were heard several

times, Lion thought it time to tell her to get back to bed. "Get into

bed," he called. "You will catch cold."

We heard the steps again and Lion rushed upstairs bearing an oil

lamp. Adelaide was in bed. "Must be rats," he decided. "Gosh,

that's a pleasant thought," was my comment.

We did not hear the steps again for some days, but after that we

heard them when we were together and when we were alone. Adelaide heard

them and thought they were her daddy's.

They weren't.

The County Comes to Call

Every afternoon for the first six weeks we had callers, who left

cards, stayed exactly fifteen minutes - no more, no less. Most of them

acted as if we were something less than human. "So Colonial, my dear,"

was how they expressed it. We made the mistake of openly admitting that

we had enjoyed our years in Canada. That was bad. It marked us as show

offs. Perverts, Socialists, and by no means entirely English.

Lion was upset because he was high church. Suffolk is extremely low.

Lion was a stubborn man at the best of times. He would not back down even

an inch if he felt in the right and he certainly would not back down and

say that Canada was inferior to England. "Different" he would

have settled for, but "inferior," not on your life.

I was suspect because I was young and full of health and vigor. I

had my share of good looks and the Irish have a knack of putting forward

the best side. This was construed to mean everything that I did not mean.

If I said hello to a man and asked him how he felt, his wife immediately

thought I was setting my cap at [him]. This used to make Lion laugh very

much at times, because he knew that there were very few men I even liked

to talk to. Not really liked that is. I liked to listen to the talk of

the educated men, but the men in Suffolk were not worth listening to. Their

minds were not concerned with education, to say the least of it.

At the close of the calling period, Lion and I set out to return

the calls, and when we had done so we breathed a sigh of relief. In Suffolk

at that time, due to the distance, one call per year made and returned

was all that was required.

It was like pages out of long forgotten books. Lion and I used to

laugh so much over some of the incidents. We did not at the time realize

that not only were we just as odd to the natives, but we were suspect as

well.

We laughed too much.

During the calling period we had not done much toward getting down

to serious work of any kind. We decided to let things go until after the

New Year. We put in an enormous amount of work on the house, though. It

was a large house, but one of the easiest homes I have ever lived in to

manage. I had the help of a Mrs. Pearson in the afternoon. She scrubbed

and helped do much of the harder work.

When we had settled in, the house looked rather like a bare hotel

with a sort of resiny kind of paint on all the doors - the kind that most

nonconformist chapels in England have on their wainscoting. We decided

to alter all that and said so to Sir George Whitehouse, who was the rector's

warden at that time. Sir George promptly told us that we could not alter

the paint without calling a parish meeting. We mentioned that we wanted

to fix up the floors with wax and varnish the way we had in Canada.

Sir George said we could not do so without calling a meeting and

having it all approved. He also told us we could not drive nails in the

walls without the consent of the vestry. (We had no intention of amusing

ourselves with this practice.) Among other things Sir George told us was

the fact, "You are not allowed to keep a goat on the lawn." Lion

was indignant and almost screamed at the dear old man. "I have no

intention of keeping a goat on the lawn or anywhere else for that matter."

Lady Whitehouse also told us many other things we were not to do.

Lion began to fume and fuss over the curtailment and was as easy to handle

as a horned toad. Until we realized that Sir George never remembered what

he had said for two minutes.

We had become accustomed to the footsteps, and we were not particularly

afraid. Lion had known that Borley was haunted. From the time he stayed

there as a young boy the idea was familiar to him and he accepted it. I

know that there are certain places where the unquiet ones have to come

from time to time. I am familiar with that from Old Ireland.

What did irk us, however, was the way folk ran in and out to the

bathroom. I began to lock the front door. This discouraged the people from

using the front hall during the week days, but on Sundays it was different.

There was one who used the front hall, but who did not go out the

front door. He - an old man with stooped shoulders and an aquiline face

- used to walk through the study and up the stairs. Sometimes I would see

him come down the stairs and go through the study. Once, I followed him

out through the study and noticed that he used the path which led down

to the part of the garden that was owned by Mrs. Ivy Bull. Another time

I saw him in the summer house, and both Adelaide and I saw him go often

into the churchyard. He wore a queer kind of long top coat with braid on

the lapels. I asked Mrs. Parson who the old man was who wore such a garment.

She turned a queer kind of greenish white and gasped, "Mr. Harry.

He did wear such a garment."

I talked to Lion about the matter and he advised me not to mention

it to anyone. I didn't until much later, after Lion had talked to someone

about it.

Noises were heard quite frequently that spring, but it was not until

June that we really had serious trouble.

Lion began to use the Scottish Litany according to the Laud Prayer

Book of the Anglican Church. We prayed for protection against things that

go bump in the night. We then began to do the house over using a paint

that a crazy German-Canadian had taught us how to mix. The hall began to

really look like something. We thought it had a medieval flavor, with my

big oak chests and the huge pottery vases Lion bought very cheaply form

his brother Arthur, who had inherited them from his mother.

In this theme we continued to "change the place" and Lion

conceived the idea of making over a tiny dressing room at the top of the

front hall into a little chapel. We had one at Salmonhurst in Canada, and

one in Sackville. But this one at Borley we did up grand. There was a workman

living nearby who made the altar rails, and I sent to McCaw, Stevenson

and Orrin, Belfast for the paper which made the plain glass into stained

glass.

Unfortunately, however, Lady Whitehouse - who always walked into

the house on Sunday and up the stairs to the bathroom - saw the chapel,

or prayer room, and disapproved. However, Sir George for some reason or

other thought it was all right because we did not have chairs in it.

The Bulls

The Bull family were delightful folk. Relics of a long past culture.

They would have been perfectly at home in the age of Dickens, or even earlier.

Each member of the family was different in character. Freda was the eldest

of the family, I believe. She was the housekeeper and had charge of the

servants, money, and made all the arrangements.

Kathleen was the adventurous one. She drove an automobile. Ethel

"kept hens." Elsie was a widow, very much so. Milly lived away

from home and was a market gardener. Constance was regarded as "backward"

by her family and was treated accordingly. Actually, she was kind of charming.

Alfred was a schoolmaster - of the Mr. Chips type. Gerald ran a laundry

and was considered the unconventional one. There was a brother whom they

had not heard from for many years. He was believed to be, "in trade."

He was not mentioned.

They lived in Cornard Lodge, or the dividing line between Sudbury

and Cornard Magna. Some of them believed firmly that Borley was haunted,

and had some juicy tales to tell. Others did not, or professed to not believe.

Harry, the preceding rector of Borley [prior to the Smiths],

had married a widow. He would not allow [her] daughter to live in family

with them. When not on boarding school, she had her own apartment in the

school room wing. Some of the Bull's liked Harry's wife, some of them hated

her. She was a pleasant and charming person and her daughter delightful.

Her life at Borley was far from happy.

We Meet Obstacles

At this time we were having quite a difficulty in keeping the house

free from rocks and pieces of iron. The rocks were generally of the sizes

of large pumpkins, and the pieces of iron were odd looking items, the likes

of which neither Lion nor myself were familiar. At one time a huge old-fashioned

grate - which weighed nearly a hundred weight - was deposited on the stairs.

Since there were so many entrances and exits, Lion and I at first

attributed a lot of the incidents to the spite of the backward peasants.

We soon learned that some of that might me true, but that a lot of it could

not be accounted for in that way.

I suspected a certain boy, who was rather mischievous, and after

playing detective, I caught him throwing rocks on the roof. He confessed

that he had often done that, but stoutly denied that he had ever done anything

else. I believed him, since he was very frightened. He confessed that he

had got the idea of doing it from hearing stories in the Smith's time.

Incidents began to get worse and Ethel Bull at this time introduced

Lion to Harry Price.

Harry Price and His Cohorts

One of the Bulls who was especially dear to me said, "I hate

Harry Price." Since they were given to rather extravagant speech,

I did not put much stock in the statement, but when I was introduced to

him in Borley Rectory, he gave me the creeps. He had pointed ears, a balding

head with high forehead, and eyes which were startling. They were not polite

eyes.

He arrived rather late one evening and with him were two women and

a man. He wanted to spend the night at the rectory. I was against it, especially

as a man named Salter had been at the rectory in the afternoon, and greatly

advised against it. Lion insisted that Price be allowed to come, since

he - Lion - had promised Ethel to allow it.

Price at first was very charming. He and his cohort went back to

Long Melford where they were staying and planned to bring equipment. They

brought a picnic basket and had lost the male member of the party. There

was a charming lady - a Mrs. Richards her name was, I think - and a woman

named Mrs. Goldney. She was the vulgar type, who not only believed in calling

a spade a spade, but believed in knocking down women with the same instrument.

Almost her first words to me were, "You are very much younger than

Mr. F.."

This did not bother me at all, since I have known Lion since I was

five years of age and had been accustomed to knowing that he is much older

than I. She appeared not to like my being so cheerful over it. So she tried

another attack.

"You have been quite sick this past few months, haven't you.

You look healthy enough."

I told her - since she gave out that she was a nurse - that I had

suffered from a female disorder.

"What type of disorder?" she questioned unpleasantly.

"I had two operations for it," I replied. "One in

Fredericton and one in Grand Falls Hospital."

"Were they abortions?" she demanded.

"No!" I almost snarled. "It is to prevent catamenia

being continuous."

"Did your husband know the doctors?" she persisted.

"Both of them," I retorted, and added, "It was he

who arranged both operations."

At this point Mrs. Richards, who appeared to be more and more ill

at ease said, "I don't think we should discuss Mrs. F's health."

Mrs. G. got snippy at this and declared it was pertinent.

More to change the situation than anything, Mrs. Richards decided

it was time to have a lunch. The study table was called into action and

Harry Price produced a bottle of wine. Sandwiches were passed, neither

Lion nor I took sandwiches, having eaten our evening meal just recently.

Price insisted that we should have wine. Lion refused wine, since

he never drank it on any occasion. It hade his heart bump. I refused because

I did not like the company and there is no sense to drink with those one

does not like. Price pulled his wine into ink trick.

There were the incidents of the bells being rung from Adelaide's

room, though all the doors were shut.

Price and Mrs. Goldney were constantly running out together, and

I noticed glances between them that surprised me. I sneaked out of the

garden door and slipped through the side door. They got a surprise. So

did I. They were in the throes of an affair.

The party lost its interest soon after that for both Mr. P. And Mrs.

G. They said the atmosphere was not right and that they would come back

next day. They did. They both solemnly declared it was I who was the Ghost.

More Nuisances

We had barely gotten rid of Price when we were tormented by the Press.

We gave the man short shift and told him to go. He went, and after interviewing

Price printed a story - nothing to it really, just a rehash of previous

stories. The difference in ages was stressed, and the fact that I was pretty.

Edwin Whitehouse came on the scene 'round about this time. Nephew

of Sir George Whitehouse, he had received a nervous discharge from the

Navy. He had served in World War I at the age of 15 as a midshipman, and

had really been through the mill.

He was, at the time I first made his acquaintance, recovering from

a love affair. He was seriously thinking of becoming a monk. He was tall

after the fashion of the upper middle-class Englander, and pleasant enough

at first sight. Later he became a nuisance. He was forever wanting to analyze

his feelings, the reactions of others to his feelings, and religion was

his chief topic. Sin was his preoccupation.

He tried to convert Lion. Lion was very naughty about him. Whenever

he saw Edwin coming, or heard him, Lion used to fly out of the house -

anywhere - mostly he took refuge in the church. I was stuck.

To my chagrin I realized that Lady W. fancied that I encouraged Edwin.

I openly told Edwin this and he appeared delighted. I mentioned this to

Lion and he though the whole thing a joke. He said, "You should not

be so pleasant to him," and caught me in my own trap. I was constantly

telling Lion to be pleasant to people. Even when he did not like them.

Mediums from Marks Tey

Ian stayed with us 'round this time, and really led the world a merry

chase. Irish, 18 years of age and full of fun, he enjoyed himself to the

hilt. [January 1, 1933] When he was not off hunting, he was singing

through the house at the top of his lungs one minute, and the next he would

be out in the garden hunting for buried treasure.

All that he ever found were the remains of what had once been a tunnel.

It went under the road leading into the field by the churchyard. I decided

that it might have been the remains of a sewer system of an earlier time.

I forbade him to enter it. He was not the kind you can forbid much, and

traced its entrance to the cellar. I was exceptionally thankful when its

entrance caved in, and soon after that he returned to Ireland.

We had a group of people from Paddington and a group from just outside

London. They were spiritualists, and although they were kind and helpful,

I counseled Lion against having such people in the house. But he persisted.

At this time there was coming over Lion a change. He was no longer

interested in plays and play production. He gave up the pastoral play and

spent more and more time immersed in reading. His health was much the same

as usual, except that he had horrible palpitations and his rheumatism was

increasing.

He had some kind of communication with some folks at Marks Tey and

they came over to the house. They were pleasant folk and sang hymns and

held seances. I refused to sit in their seances for a long time, and then

one day I did so. There was nothing to it, and while we were in the middle

of it there were some terrific bumps.

The chapter, as they called themselves, continued to come on and

off, and one night they brought with them a man whom they said came from

Hempstead Heath, and another from - I believe - Clacton on Sea. These men

really were mediums. They later held a seance upstairs and in the night

it began to rain - torrents of it. When we got up in the morning it was

like a new world all washed clean.

The mediums told us we would not be really bothered again. We might

have little happenings, but there would never in our time be much trouble.

There wasn't. At least not to be compared with what had actually happened.

Local Superstitions and Traditions

These are really dillies, some of them, and often kept Lion and I

in stitches of laughter when we would recount them to each other.

The Four Manor Houses of Borley

Borley Manor had only a population of 136 in 1932. At one time it

was much larger. In the reign of Edward Confessor [1042-1066] it was in

the hands of Lewin, a freeman. In the Doomsday Book it is recorded in the

hands of Adelizia, a half-sister of William De Fortibus. In 1307 it went

to Edward I by exchange, and in 1346 Edward III gave it to the Convent

of Christ church of Canterbury. In 1539, at the time of the dissolution

[of the Monasteries Act of 1538], it was given to the Waldegraves.

Within the manor proper there was 811 acres and plenty of common

pasture for 130 sheep; arable land 702 acres; 15 acres of woods; manor

house land 15 acres. There were tofts [for outbuildings] of two acres each.

Extent of the manor in 1308 - stewards, clerks, reeve [official

charged with enforcement of local regulations], and tenants of the manor.

One pleasant messuage [premise], well built with 25 acres of grass.

(This is Borley Place.) Lord of manor was patron of church, worth ten pounds

yearly.

There was one water mill (still in existence) let at sixty shillings

per year. One pleasant messuage thereto (still existing). There are two

other manors still in existence. Both interesting. About Borley there are

so many things to tell about the manor houses. Some interesting and some

historical. [The above was obviously taken from some document. How

I wished I had recognized it for what it was during my prowling-about years

ago!]

The Church

Without a dedication. A beautiful little church with brasses and

tombs dedicated to long dead folk. The local story of the disappearance

of the church silver is interesting.

There is a story that the coffins in the Waldegrave crypt move. There

is the story of the tunnel from the church to the cellar. The rectory cellar

was an extraordinary place. Obviously built on an old foundation, it had

three wells in it and all kinds of crypt-like places in its domain. It

was dry as a bone and as cold as Greenland.

Animals Were Odd

We could never get a cat or dog to stay at Borley. We tried several

- the cats died and the dogs ran away. There were several incidents which

make good reading, but the fact remains we could not get a dog to stay

with us. There was, however, in the garden a very odd animal who did stay.

The gardener called it "That Owld Thing." It lived under the

summerhouse and was about the size of a large mongoose, but it was not

a mongoose. It used to appear at night on the lawn and would disappear

under the summerhouse if one approached.

Borley Village

The inhabitants are out of this world, or were. It is bypassed by

all leading arterial roads, and stays like an oasis. The children still

follow their fathers into business and the girls still talk about going

into service. It has no village store, just a post office. There is one

road through it, and all the cottages are over four hundred years of age.

Many are nearly seven hundred.

There is a cedar [tree] in the rectory garden which is many hundreds

of years of age. There are beautiful oaks and lovely trees. The churchyard

is a beautiful place with its quaint yews cut into quaint figures. The

graveyard itself is a tiny spot with bones dug up every time there is a

burial, yet the villagers resent the thought of an addition to the churchyard.

They want their bones to be with the bones of their fathers.

The Gardens of Borley

The rectory garden was both warm and cold, barren and bountiful,

according to the section in which one was in. The courtyard was as different

as chalk from cheese to the inner courtyard, and the terrace garden was

a joy.

There was a walk in the garden which was pleasant and warm, there

was a place to rest in the sun and violets grew in great profusion there.

Giant Campanulas made a blue showing, and other warm summer flowers made

the air sweetly spiced on a summers day. We called this section the jungle,

and there we could sit and read in the summer time, listening to the drone

of the bees.

Within ten feet away there was another walk, also hedged in with

box, but nothing grew. We tried all kinds of shrubs, seedlings and bulbs,

but nothing flowered. Box would grow and yew, but lilacs no. Rhododendrons,

no. No flowering shrub would grow.

Chapter Nineteen

The outlying villages near Borley are many of them just as old style

as Borley. Belchamp Walter, Belchamp St. Paul, Eyston, Pentlow and Liston,

are some of them. Suffolk owed its prosperity to the Wollen prosperity

brought over by the displaced Flemings.

Borley never felt it. It is truly rural. The people are worth a chapter.

Ghost lights in the Window

In this chapter are many incidents which will be discussed, including

the Ghost lights, the bells, and the apparitions.

Chapter Twenty One

Harry Price, Edwin Whitehouse, Mrs. Goldney, and some mediums. Mrs.

Goldney voltfaced [about-faced; reversal in policy] so often she

left me dizzy. One thing only annoyed her, she knew I knew she and Harry

were that way about each other.

Chapter Twenty Two

Miss Warren came as housekeeper to Mr. Vial (2)

and lived in the rectory at the time Lion bought the flower shop I was

to run. It would have been a good arrangement if Lion did not expect too

much. As it was, he became increasingly ill and yet wanted me to take over

as breadwinner, yet he did not want me to be away from home.

At last I couldn't stand it any more and I gave up the shop. I went

home and got a job in Ipswich, selling washing machines called Jiffy. I

did well at it and could have been made supervisor, but just at that time

Lion began to have queer fainting fits and I talked with Dr. Tyler who

said it was his heart. Lion went to the Heart Hospital in London and there

was told of his heart's bad health. It affected his speech at times, and

made it hard for him to remember. He also got very quarrelsome with everyone

but me. Then one Sunday he collapsed in church and the doctor said no more

preaching.

The house had been quiet enough for over three and one-half years

when we left Borley Rectory.(3)

More Trevor Hall research

In 1956, Ian Shaw gave testimony to Hall relating to the Borley years.

At the end of Shaw's recollections, Hall described him "in some respects

psychologically abnormal." Hall said Ian was "purposefully taught

to deceive" as a child. He knew who his real mother was, yet was raised

as her brother. Hall concluded, "how far the details were coloured

by his bias against his mother's sexual abnormality and its background

of psychic phenomena is a matter of judgement of the reader."

The English-born Frank Peerless told Ian Shaw how he had stayed in France

after WW I. He opened a shoe store in a town named Arles, and later became

"Francois d'Arles." He had also used the names "Black"

and "Wade" during his life prior to Borley. He was roughly the

same age as Lionel, making him 21 years older than Marianne.

D'Arles told Shaw he was seduced by Marianne very soon after he arrived

at Borley. According to d'Arles, he gave Marianne a ride in his motorcycle

when she asked him to stop by a field as she felt ill. Shaw heard d'Arles

describe his mother as a "sexual maniac."

Shaw said d'Arles and Marianne wore wedding bands engraved with the

names "Marianne and Francois Uniter." Marianne adopted a baby

- John Evemond Emery - and when d'Arles told Shaw the child was definitely

his, Ian was convinced he was telling the truth. A new Borley researcher

has discovered evidence that seems to support the claim by d'Arles that

the child really was his - as the result of an affair with the child's

mother, Marjorie Emery!(4)

Shaw told Hall that Marianne used to tease Francois by putting face

powder on the back of her hand and pretending to sniff cocaine.

Lionel Foyster was very critical of every penny, according to Shaw.

If Marianne wanted a dress and her husband would not buy it, she would

buy material and pretend to sew a duplicate. She would then secretly buy

the original. "Shaw was convinced that Mr. Foyster never had the slightest

inkling regarding his wife's real character or her mode of life,"

Hall wrote in his unpublished manuscript. "He was completely trustful,

believing everything that Marianne told him, and would re-tell her descriptions

of incidents as if he had experienced them himself. He was infatuated with

his wife and was unhappy if she was away from him for a few hours. He was,

in Shaw's view, completely hoodwinked throughout the whole of his married

life."(5)

Shaw explained to Hall how some of the paranormal events at Borley may

have originated, and told him "Foyster believed wholeheartedly in

the ghosts." Shaw claimed it was d'Arles who upbraided Marianne by

saying the "deception was getting out of hand and must stop."

A more comprehensive analyses of the Borley haunting will be taken up

in a later volume, but Hall made a couple of observations that bear mentioning

at this time:

1. Shaw was not present at Borley during the 1930-1932 period when most

of the phenomena reportedly occurred.

2. Most of what Shaw related to Hall was told to him originally by d'Arles.

Hall called such testimony "suspect."

Further, Shaw told Hall in two letters written in 1956:

I have an antipathy towards spiritualism or anything which leans

toward the supernatural. I believe that it is a sure means of attracting

weak-minded people and relieving them of their capital.

This whole business is founded on a mass of falsehoods and deception,

and ranks equal to any sordid case reported from the dregs of society.(6)

Shaw concluded his interview with Hall by claiming d'Arles and Marianne

started the flower shop as man and wife. He also claimed d'Arles had an

affair with a 16 year old girl, and started his own flower shop in Wimbledon.

Shaw heard a rumor that Marianne had d'Arles imprisoned for blackmail,

but didn't know if that story was true or not. (7)

After finishing the Shaw interview, Hall next tracked down Mr. and Mrs.

F.M. Fenton, neighbors of Marianne during the flower shop days.

Hall said Mrs.

Fenton was "perhaps the supreme example in this case-history of Marianne's

skill in persuading otherwise sensible people that her fantastic stories

were true. . .In her view, the contradictory documentary evidence [displayed

by Hall] was false, and was accounted for by the fact that Marianne was

a member of the British Secret Service. . .and that her apparently irregular

and lascivious life was a deliberate smoke-screen for her gallant under-cover

activities on behalf of her country!"(8)

Hall said Mrs.

Fenton was "perhaps the supreme example in this case-history of Marianne's

skill in persuading otherwise sensible people that her fantastic stories

were true. . .In her view, the contradictory documentary evidence [displayed

by Hall] was false, and was accounted for by the fact that Marianne was

a member of the British Secret Service. . .and that her apparently irregular

and lascivious life was a deliberate smoke-screen for her gallant under-cover

activities on behalf of her country!"(8)

Mrs. Fenton recalled that Marianne earned the Distinguished Service

Order which she frequently wore later on.

Hall described the Fentons as "decent, clean and respectable people

of Jewish extraction" who owned the chemist shop on Worple Road near

the flower shop. Marianne became friends with her neighbors, and referred

to Mrs. Fenton as "Billy."

The story Marianne told Billy had some familiar parts to it, but also

added a few new twists. Marianne had seven or eight Christian names, and

was the child of Santiago Monk and the Countess Sarah von Kiergraff. Monk

was English, and now working in the Chilean Government. The countess was

from Schleswig-Holstein. The couple met in Denmark. Marianne spoke several

languages quite well.

Because her father traveled so much, she told Billy, Marianne was raised

by Reverend Foyster and an aunt. She was a graduate of Cambridge.

When Foyster moved to Canada, Marianne went along. Foyster adopted a

child named d'Arles Foyster. Reverend Foyster wished deeply that Marianne

would marry the boy, but she fell in love with someone named Laurenz. However,

she broke off her engagement to Laurenz and married d'Arles Foyster. The

couple had twins, Adelaide and Francois Junior.

Her husband was very mean, Marianne told Billy, and even though she

was a Roman Catholic she divorced him. He took off with a 16 year old,

and they parted company. Francois junior died shortly thereafter.

Marianne tempted fate by not only visiting the Fentons after leaving

the flower shop, but by having Billy over for visits at Borley and at Snape.

The Fenton children also stayed with Marianne, sometimes for several weeks.

Mrs. Fenton was positive Lionel told her how happy he was d'Arles was

gone and Marianne had married Fisher. Unfortunately, Fisher turned out

to be "a lazy good-for-nothing" who was dependent on Marianne

because he did not work.

Mrs. Fenton showed Hall a letter from Marianne and gave him several

pictures. Her faith in her friend was shaken only momentarily when she

realized Marianne must have made a mistake when she said Astrid had died

while living in a convent. Other than that, she was convinced Marianne

was a heroine.

Hall presses forward

Trevor Hall learned that Mary Dytor was a nurse-companion at Borley

for six months in 1932. He interviewed her in 1953 and was given some details

of her stay at Borley. She claimed she was fond of Marianne and "sympathized

with her dislike of the lonely house."

Dytor was absolutely convinced that John Evemond Emery was the son of

Marianne and d'Arles. For a while, so was Hall. Dytor said she saw both

d'Arles and Marianne place flowers on the grave.

After tracking down the child's birth and death certificates, Hall wondered

if they had been dreamed up by Marianne. The middle name - Evemond - was

not on the birth certificate, only on the notice of death. Hall made much

of the similar initials between the supposed mother, Marjorie Ada

Ruth Emery and Marianne Emily Rebecca.

Still, he was unsure, and finally decided the baby was probably adopted.

The nurse maid did not like Francois. As Hall reported, "Miss Dytor

disliked and distrusted Mr. d'Arles and regarded him as the cause of much

of the frequently strained atmosphere of the rectory household which he

dominated. . . Marianne seemed to fear and dislike d'Arles."(9)

At one point, d'Arles told Dytor that Marianne was a drug addict.

Foyster needed two sticks to walk, according to Dytor, as he was badly

crippled. He enjoyed the children very much, and "fussed" over

his wife. He was quite jealous of d'Arles.

Foyster read most of his Fifteen Months manuscript to Dytor.

He was strict with the money, and sometimes cooked odd meals such as rice

and macaroni boiled together.

Ian told Hall that Dytor "knew a great deal more" about the

affairs at Borley. Ian also told Hall that Marianne implied in a letter

that Dytor "joined in the general fun at Borley by having an affair

with a clergyman." Hall wrote in his unpublished manuscript that he

had "no evidence which supports either of these suggestions."(10)

Some objectivity

Marianne was born at the end of the Victorian era, lived through the

peaceful reign of Edward VII, and took an active part in WW I. Then came

the awful depression years - the same years she was at Borley were also

the worst period financially for all of England. She was raised in poverty

and then was thrust into world-wide shortages while at Borley. Survival

was vital - a visit by spooks would have been a welcome relief! A story

about spooks told around the fireplace surely wouldn't have been out of

place.

As Marianne has told investigators, the paranormal experiences at Borley

were a small and insignificant part of her life. As Iris Owen told me,

"She could never understand why everyone made such a fuss. I think

she was genuinely puzzled over the interest the phenomena generated. She

felt persecuted that because of that interest her private life was exposed

in such detail. In those times, there were plenty of people whose private

lives would not bear that kind of inspection. They were very disturbing

and frightening times in which to live."

Marianne told a private investigator that:

"I was happy at Borley. [It] was an isolated house and we had

no power and no servants, but we did have one or two parties which were

well attended, and I never thought of people as disliking me.

"I made a garden there, and it was certainly an improvement

on the places I had lived in New Brunswick - it definitely was quite an

improvement.

"If we could stick Salmonhurst, then we could certainly stick

Borley Rectory. It was like coming, well, from darkness into light. As

to it being out of the way, that didn't bother me. I have never lived in

towns, nor have I any wish to.

"During part of the time at the rectory, I had a great deal

of trouble. . . with menstrual flowing, which went over a long period.

I did have several collapses there, which can be corroborated by Dr. Alexander

of Sudbury.

"I don't remember a great deal about many [paranormal] incidents,

but I do recall when Mrs. Goldney was there on [one] occasion. I was ill

when they arrived, and I'd been flowing, and I was ill. When I would have

those long flows I would faint, which I don't think is anything unusual.

Certainly Dr. Alexander didn't feel it was unusual, and Lionel helped me

up to bed. She said, 'There's nothing wrong with her, there's nothing wrong

with her.'

"Well, Lionel knew that there was and he didn't pay much attention

to her.

"I was put in my room, and I believe there were some incidents

of stone throwing."(11)

Marianne's role in the hauntings

The details of the haunting at Borley will be discussed in a subsequent

volume, but one interesting aspect of the haunting revolves around Marianne's

role. As Iris Owen has said many times, "she herself never

made any claims about paranormal events." In an October 4, 1979 letter

to Peter Underwood, Owen said, "I frankly do not see that it matters

whether Marianne can be believed or not, since she was not the one making

the claims - it was Foyster himself, and [Harry] Price." Reverend

Foyster told Price things Marianne had supposedly said, and Foyster wrote

those alleged events in his various journals. There is no way of knowing

what Marianne actually told Foyster, or if anything she did tell

him was meant in fun. There is no public record of any claims many directly

by Marianne. In actual fact, as Owen explained to Underwood in that

same 1979 letter, Marianne was "aggrieved that no one has ever asked

her for her own version of the events."

In her own papers, Owen jotted down. "If Trevor [Hall] brings out

his book, further writing about her could look like persecution."

Hall did not write the book, but Robert Wood did.

Chapter Eight

Table of Contents

1. Owen, Iris M., Mitchell, Pauline. Marianne's

Story. Toronto: New Horizons Research Foundation, 1978. pp. 33-62.

2. Donald Frederick Pratt Vial. This name appears

in no other Borley literature. Alan Roper discovered the name on an electoral

register dated about 1934. Vial died June 2, 1979 apparently without speaking

to anyone about Borley.

3. Hall, Trevor. Marianne Foyster of Borley Rectory.

Unpublished, 1958. Vol. V, appendix.

4. Kemp, Paul.

5. Hall, op. cit. Vol. II, p. 22.

6. Ibid, p. 24.

7. Hall did not do as thorough a job as he might

have done in researching Pearless. Alan Roper cleared up several details

with his research, however. He told me, "Pearless married Ada Ewens

in 1918. She divorced him in 1934 and moved with their three children to

America. In the late 20's, Pearless was living with a woman called Kate

Emily Fernie in Wood Green, London. She was the mother of Francois Jr.

- born July 31, 1928 - who was brought to Borley. Pearless married Jessie

Irene Dorothy Mitchell August 4, 1934, and they had two children. She divorced

him in 1944. Pealress then married Jessie Steed November 10, 1944, and

they had one daughter."

8. Hall, op. cit. p. 27.